From the color of your eyes to key personality traits, genes determine a lot about you. Our genes contain coded messages that tell the cells in our body how to behave, controlling how we grow and develop. We have around 25,000 genes in our bodies that are passed down from parents to children. So can cervical cancer be hereditary and passed from mother to child? Read on to find an answer.

-

Tracking cycle

-

Getting pregnant

-

Pregnancy

-

Help Center

-

Flo for Partners

-

Anonymous Mode

-

Flo app reviews

-

Flo Premium New

-

Secret Chats New

-

Symptom Checker New

-

Your cycle

-

Health 360°

-

Getting pregnant

-

Pregnancy

-

Being a mom

-

LGBTQ+

-

Quizzes

-

Ovulation calculator

-

hCG calculator

-

Pregnancy test calculator

-

Menstrual cycle calculator

-

Period calculator

-

Implantation calculator

-

Pregnancy weeks to months calculator

-

Pregnancy due date calculator

-

IVF and FET due date calculator

-

Due date calculator by ultrasound

-

Medical Affairs

-

Science & Research

-

Pass It On Project New

-

Privacy Portal

-

Press Center

-

Flo Accuracy

-

Careers

-

Contact Us

Is Cervical Cancer Hereditary? Cervical Cancer Genetics Explained

Every piece of content at Flo Health adheres to the highest editorial standards for language, style, and medical accuracy. To learn what we do to deliver the best health and lifestyle insights to you, check out our content review principles.

The American Cancer Society estimates that over 4,000 people in the U.S. will die from cervical cancer in 2021. When cervical cancer is detected in the pre-cancer stage or early-stage cervical cancer, it’s highly treatable and has a good prognosis. That’s why getting regular gynecological checkups is so important.

The first warning signs of cervical cancer often involve abnormal vaginal bleeding, abnormal vaginal discharge, and pain during intercourse. Your genetics may also hint at whether you’re more at risk to develop this disease. But is cervical cancer genetic? Let’s take a closer look and explore the role your genes play when it comes to cervical cancer.

Can cervical cancer be passed from mother to child?

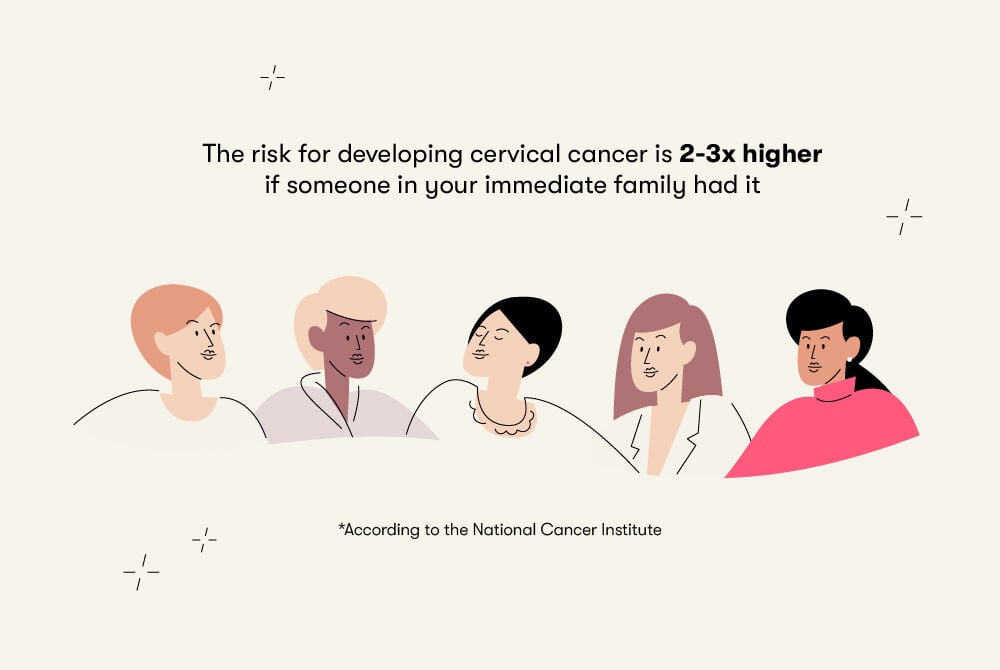

Is cervical cancer hereditary? This question has motivated scientists for years. Research has shown a cervical cancer genetic link between both the body’s ability to fight off a human papillomavirus (HPV) infection and the risk of developing certain rare forms of cervical cancer. According to the US National Cancer Institute, your risk of developing cervical cancer is 2–3 times higher if someone in your immediate family has been affected.

Cancer develops when something goes wrong with one or more of the genes in a particular cell, called a “fault” or a “mutation.” Gene mutations can occur naturally in the body over time or can be inherited genetically.

Without a mutation, the gene would protect us from cancer by fixing DNA damage that naturally occurs when cells split and grow. But inheriting a faulty version of one of these genes means that it won’t be able to repair damaged DNA.

The vast majority (99 percent) of all cervical cancer cases are due to infection with a high-risk strain of HPV. Studies have shown that inheriting certain faulty genes (immune response genes and DNA repair genes) make it more difficult for the body to clear an infection with HPV, thereby increasing the risk for cervical cancer. Genes that raise the risk of cancer are known as cancer susceptibility genes.

Most people (70–90 percent) are able to fight off an HPV infection on their own without treatment within one to two years. But if faulty genes are stopping your body from fighting the infection, it may not go away and could develop into cervical cancer over time.

A 2009 study found that some DNA repair genes increase the risk for cervical cancer, while other immune responsive genes and DNA repair genes decrease the risk. A 2010 study confirmed these findings. A 2011 study also found that cervical cancer risk was higher in women who had problematic immune response genes, which can be passed down from mother to child.

Additionally, people from the same family may share certain non-genetic risk factors for cervical cancer, such as smoking.

If people across generations in your family have been diagnosed with cervical cancer, make sure to speak with your health care provider about your risk factors and family medical history. Although it may not be clear if the cancer diagnoses were caused by genetic or non-genetic factors, having regular Pap and HPV screening tests can accurately determine your risk.

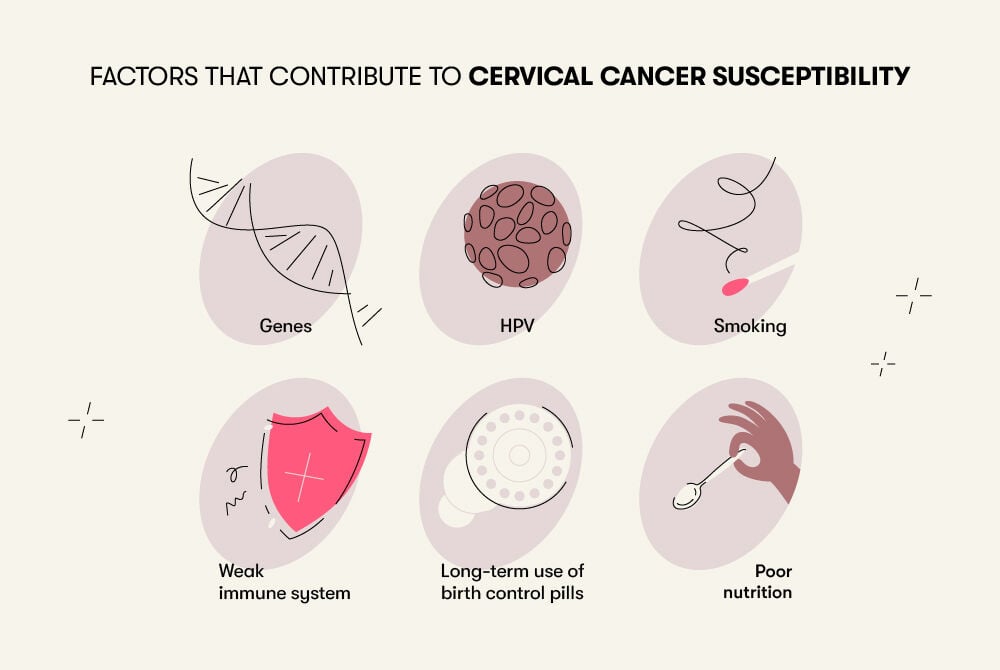

What factors contribute to cervical cancer susceptibility?

The main risk factor for developing cervical cancer is infection with a high-risk strain of HPV. But getting HPV doesn’t necessarily mean that you will develop cervical cancer. There are also other factors that increase the risk for cervical cancer.

The following factors raise the risk of developing cervical cancer:

- Genes

- HPV

- Smoking

- Weak immune system

- Long-term use of birth control pills

- Eating a diet low in nutrients (with few vegetables and fruits)

What can minimize the risks?

When it comes to preventing cervical cancer, one thing you can do is get regular Pap and HPV screenings.

To prevent HPV, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention and the World Health Organization recommend getting vaccinated. The Gardasil vaccine has been approved by the FDA and helps prevent cervical cancer caused by common strains of high-risk HPV. It’s available for people between the ages of 9 and 45. But it’s most effective when administered before the onset of sexual activity.

For early detection of cervical cancer, health care providers recommend getting a Pap test every three years. In addition, experts recommend reducing your risk by:

- Practicing safe sex, such as by using condoms

- Quitting or avoiding smoking

Also, taking care of your overall health can prime your body to fight infection and function in the best way possible. Healthy parents are more likely to have healthy babies, which may also lower their children’s risk of developing cervical cancer.

Summing up

Scientists have found a genetic link to cervical cancer. Certain faulty genes make it more difficult for the body to fight off HPV, the main cause of cervical cancer cases. Other genetic issues increase the risk of developing rare forms of cervical cancer.

To maximize your chance of avoiding cervical cancer, get regular Pap tests and HPV screenings and get the HPV vaccine if you haven’t already. You can also lower your overall risk by quitting or avoiding smoking and practicing safe sex.

Hey, I'm Anique

I started using Flo app to track my period and ovulation because we wanted to have a baby.

The Flo app helped me learn about my body and spot ovulation signs during our conception journey.

I vividly

remember the day

that we switched

Flo into

Pregnancy Mode — it was

such a special

moment.

Real stories, real results

Learn how the Flo app became an amazing cheerleader for us on our conception journey.