Progesterone is a hormone that plays a big role in the female body. When this hormone is out of balance, it can lead to some health problems. Read on to learn the signs and causes of low progesterone and how to increase progesterone levels.

-

Tracking cycle

-

Getting pregnant

-

Pregnancy

-

Help Center

-

Flo for Partners

-

Anonymous Mode

-

Flo app reviews

-

Flo Premium New

-

Secret Chats New

-

Symptom Checker New

-

Your cycle

-

Health 360°

-

Getting pregnant

-

Pregnancy

-

Being a mom

-

LGBTQ+

-

Quizzes

-

Ovulation calculator

-

hCG calculator

-

Pregnancy test calculator

-

Menstrual cycle calculator

-

Period calculator

-

Implantation calculator

-

Pregnancy weeks to months calculator

-

Pregnancy due date calculator

-

IVF and FET due date calculator

-

Due date calculator by ultrasound

-

Medical Affairs

-

Science & Research

-

Pass It On Project New

-

Privacy Portal

-

Press Center

-

Flo Accuracy

-

Careers

-

Contact Us

Low Progesterone Symptoms, Causes, and What You Can Do About It

Every piece of content at Flo Health adheres to the highest editorial standards for language, style, and medical accuracy. To learn what we do to deliver the best health and lifestyle insights to you, check out our content review principles.

How to tell if you have low progesterone

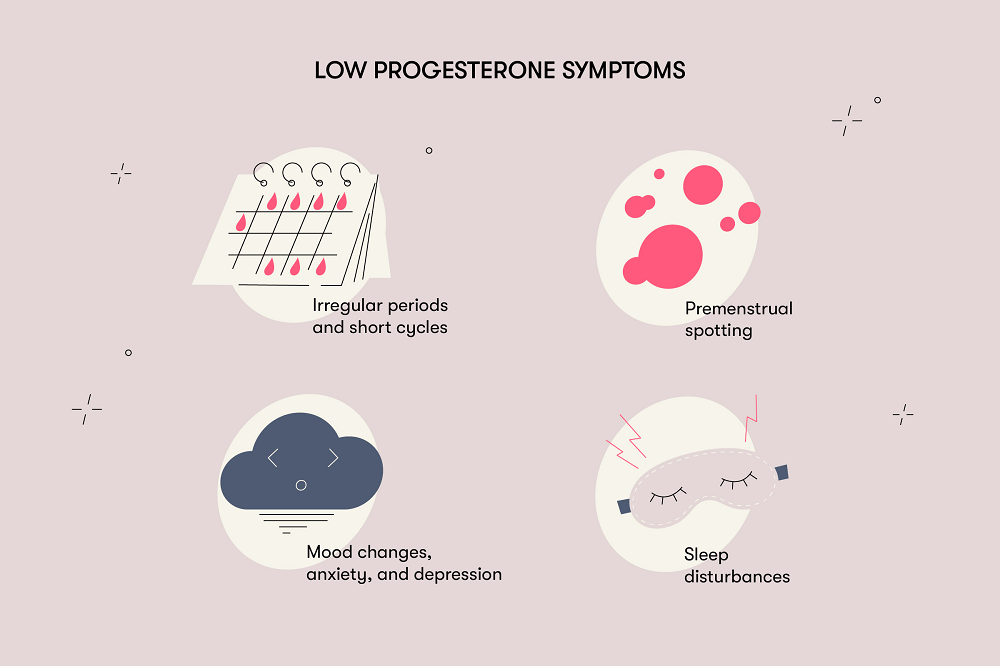

The most noticeable manifestation of low progesterone levels is irregular periods and short cycles, but sometimes symptoms like premenstrual spotting may appear. Other symptoms may include mood changes, sleep disturbances, anxiety, and depression.

Progesterone affects the regulation of fluid levels in the body. That’s why weight gain due to fluid retention and breast tenderness are possible with decreased progesterone levels, although this is rare.

In a healthy body, estrogen and progesterone naturally balance each other out. Having low progesterone causes estrogen dominance, which leads to an overgrowth of the lining of the uterus (endometrium), which in turn causes heavy periods.

What’s the normal level of progesterone?

Progesterone levels change throughout the menstrual cycle. Here’s how they change, starting from the first day of the cycle, which is the first day of menstrual bleeding.

In the first part of the menstrual cycle, the follicular phase, the level of progesterone is low and shouldn’t exceed 0.89 ng/ml. During ovulation, progesterone rises to 12 ng/ml, but it may be less than this. After ovulation, the corpus luteum begins to work, and during this part of the cycle there’s a sharp increase in the level of progesterone.

The second part of the menstrual cycle, the luteal phase, is the part of the cycle that happens after ovulation. It’s the phase with the highest progesterone levels — 1.8-24 ng/ml. The peak of progesterone generally occurs between days 21–23 of the menstrual cycle.

Checking the progesterone levels during this time is one way to tell if ovulation took place. Basically, a level of progesterone that’s more than 10 ng/ml indicates normal ovulation, but if progesterone is lower than that, it means ovulation didn’t happen or the corpus luteum didn’t produce enough progesterone after ovulation.

In a menstrual cycle when pregnancy doesn’t occur, the corpus luteum stops working, which causes progesterone levels to drop sharply. Usually around four days before a period begins, the level of progesterone is back down to the level it was at for the first phase of the cycle.

If pregnancy occurs, the progesterone level will increase over time as the fetus develops. In the first trimester, it will reach levels of 11–44 ng/ml.

During pregnancy, progesterone levels below 5 ng/ml are considered abnormal. Additionally, birth control that suppresses ovulation — like the pill, patch, or ring — can also cause low progesterone levels. This is because this kind of birth control prevents ovulation from occurring, so there’s no corpus luteum to make progesterone.

Progesterone levels naturally decline with age. This tends to coincide with a decline in fertility and the onset of menopause. Decreased production of progesterone with age affects the menstrual cycle, making it anovulatory and irregular. The intervals between periods gradually lengthen, and then periods stop entirely with the onset of menopause.

Generally, progesterone is detected via a serum blood test carried out by a health care provider. However, there are some at-home lab tests you can perform to check your progesterone levels. Discuss your options with a health care provider to determine what works best for you.

What causes low progesterone

There are a few reasons you might have low progesterone symptoms or test positive for low progesterone. Some of the most common reasons include:

Take a quiz

Find out what you can do with our Health Assistant

1. Anovulatory cycle

An anovulatory cycle is a cycle when ovulation doesn’t occur. Since no egg is released, there isn’t an empty follicle (the corpus luteum) left behind to produce progesterone. This is common in folks with PCOS and people on certain types of birth control.

2. Hypothyroidism

While low progesterone may lead to thyroid issues, problems with the thyroid may also cause low progesterone. Hypothyroidism is when the thyroid is underactive. This means that the hormones that regulate your endocrine system aren’t produced in high enough amounts, which means it can be difficult for your body to produce enough progesterone.

3. Increased cortisol levels

When the body produces high amounts of cortisol (AKA the stress hormone), it basically “steals” the resources required to make progesterone. This means that chronic stress can make it difficult to produce enough progesterone.

4. Hyperprolactinemia

This condition is caused by increased production of the hormone prolactin by the pituitary gland. Prolactin negatively affects the production of sex hormone precursors, thereby leading to a decrease in progesterone synthesis and disruption of the menstrual cycle (up to complete absence of menstruation). In simple terms, when there’s too much prolactin, the body produces less progesterone. This can disrupt the menstrual cycle and even cause periods to stop entirely.

5. Low cholesterol levels

The body needs cholesterol to make progesterone. So without enough cholesterol, the body can’t make enough progesterone.

How to increase progesterone

If you’re reading the signs and suspecting you might have low progesterone, you may be wondering how to increase progesterone. A few treatment methods include:

- Progesterone creams — These medications need to be prescribed by a health care provider. It’s a gel that usually comes in dosed applicators to make it easy to use. It’s inserted into the vagina every other day for up to six doses unless your health care provider recommends otherwise.

- Oral progesterone pills —These pills can be used for irregular menstrual cycles and uterine bleeding. The dose and duration of administration will be determined by your health care provider.

- Vaginal suppositories — These are inserted once or twice a day.

If you don’t know what to do about your low progesterone symptoms, discuss your options with a health care provider. They can help you determine the best course of treatment for you and your body.

Summary

Progesterone is an important hormone in the female body. When it’s out of balance, it can affect your health and menstrual cycle.

Low progesterone levels can be caused by things outside of the reproductive system, such as cholesterol levels and thyroid, pituitary, and adrenal gland issues. Once a medical professional determines what’s causing low progesterone, they can prescribe the appropriate treatment.

Your menstrual cycle can offer unique insights into your body, guiding you toward improved health and wellness and a better life.

Hey, I'm Anique

I started using Flo app to track my period and ovulation because we wanted to have a baby.

The Flo app helped me learn about my body and spot ovulation signs during our conception journey.

I vividly

remember the day

that we switched

Flo into

Pregnancy Mode — it was

such a special

moment.

Real stories, real results

Learn how the Flo app became an amazing cheerleader for us on our conception journey.

References

Haas DM, et al. “Progestogen for Preventing Miscarriage.” Cochrane, 20 Nov. 2019, www.cochrane.org/CD003511/PREG_progestogen-preventing-miscarriage.

“Women's Reproductive Health.” Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, 28 Apr. 2020, www.cdc.gov/reproductivehealth/womensrh/index.htm.

Li, Sophie H., and Bronwyn M. Graham. “Why Are Women so Vulnerable to Anxiety, Trauma-Related and Stress-Related Disorders? The Potential Role of Sex Hormones.” The Lancet Psychiatry, vol. 4, no. 1, Elsevier BV, Jan. 2017, pp. 73–82. Crossref, doi:10.1016/s2215-0366(16)30358-3.

Daya, Salim. “Efficacy of Progesterone Support for Pregnancy in Women with Recurrent Miscarriage. A Meta-Analysis of Controlled Trials.” BJOG: An International Journal of Obstetrics and Gynaecology, vol. 96, no. 3, Wiley, Mar. 1989, pp. 275–280. Crossref, doi:10.1111/j.1471-0528.1989.tb02386.x.

Palomba, Stefano et al. “Progesterone administration for luteal phase deficiency in human reproduction: an old or new issue?.” Journal of ovarian research vol. 8 77. 19 Nov. 2015, doi:10.1186/s13048-015-0205-8

Alderson, Thomas. “Luteal Phase Dysfunction Treatment & Management.” Medscape, WebMD LLC, 12 July 2021, https://emedicine.medscape.com/article/254934-treatment#d9

Shah, Duru, and Nagadeepti Nagarajan. “Luteal insufficiency in first trimester.” Indian journal of endocrinology and metabolism vol. 17,1 (2013): 44-9. doi:10.4103/2230-8210.107834

Sokhadze, Khatuna et al. “Reproductive function and pregnancy outcomes in women treated for idiopathic hyperprolactinemia: A non-randomized controlled study.” International journal of reproductive biomedicine vol. 18,12 1039-1048. 21 Dec. 2020, doi:10.18502/ijrm.v18i12.8025

“Progestin (Oral Route, Parenteral Route, Vaginal Route).” Mayo Clinic, Mayo Foundation for Medical Education and Research (MFMER), 1 August 2021, https://www.mayoclinic.org/drugs-supplements/progestin-oral-route-parenteral-route-vaginal-route/description/drg-20069443

Al-Chalabi, Mustafa et al. “Physiology, Prolactin.” NCBI, StatPearls Publishing LLC, 29 July 2021, https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK507829/

“Test ID: PGSN. Progesterone, Serum.” Mayo Clinic Laboratories, Mayo Clinic, August 2021, https://www.mayocliniclabs.com/test-catalog/Overview/8141

Cable, Jessie and Michael H. Grider. “Physiology, Progesterone.” NCBI, StatPearls Publishing LLC, 9 May 2021, https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK558960/

“Changes in Hormone Levels.” NAMS, The North American Menopause Society, Harvard Health Publications, 2010, https://www.menopause.org/for-women/sexual-health-menopause-online/changes-at-midlife/changes-in-hormone-levels

Stachenfeld, Nina S. “Sex hormone effects on body fluid regulation.” Exercise and sport sciences reviews vol. 36,3 (2008): 152-9. doi:10.1097/JES.0b013e31817be928