Uterine fibroids affect more women and people with periods than you might think, but what do they feel like? And do they go away? We asked the Flo community to share their experiences of living with fibroids.

-

Tracking cycle

-

Getting pregnant

-

Pregnancy

-

Help Center

-

Flo for Partners

-

Anonymous Mode

-

Flo app reviews

-

Flo Premium New

-

Secret Chats New

-

Symptom Checker New

-

Your cycle

-

Health 360°

-

Getting pregnant

-

Pregnancy

-

Being a mom

-

LGBTQ+

-

Quizzes

-

Ovulation calculator

-

hCG calculator

-

Pregnancy test calculator

-

Menstrual cycle calculator

-

Period calculator

-

Implantation calculator

-

Pregnancy weeks to months calculator

-

Pregnancy due date calculator

-

IVF and FET due date calculator

-

Due date calculator by ultrasound

-

Medical Affairs

-

Science & Research

-

Pass It On Project New

-

Privacy Portal

-

Press Center

-

Flo Accuracy

-

Careers

-

Contact Us

What do uterine fibroids feel like, and do they go away?

Every piece of content at Flo Health adheres to the highest editorial standards for language, style, and medical accuracy. To learn what we do to deliver the best health and lifestyle insights to you, check out our content review principles.

Uterine fibroids — growths of smooth muscle of different sizes found in the uterus — are pretty common, so much so that 70% of women will develop at least one fibroid during their reproductive years.

And, since only around one-third of fibroids are big enough for a health care provider to spot in a checkup, not everyone who has fibroids is even aware that they have them.

Key takeaways:

- Uterine fibroids are noncancerous growths that affect as many as 70% of women.

- They vary in size and don’t necessarily cause any symptoms.

- When symptoms do occur, they can include pelvic pain, back pain, constipation, and heavy periods.

That said, those who do have uterine fibroids — the symptom-causing kind — have plenty of replies in answer to the question: What does a fibroid feel like? That’s because their fibroids can be accompanied by an array of signs.

Read on to find out more about fibroids, including what they are, signs you might have them, and if fibroids go away on their own.

Take a quiz

Find out what you can do with our Health Assistant

What are fibroids?

Fibroids are solid tumor-like growths of the smooth muscle that grow in and around your uterus. The word “tumor” might sound scary, but rest assured that fibroids are not cancer — and having them doesn’t increase your risk of developing uterine cancer.

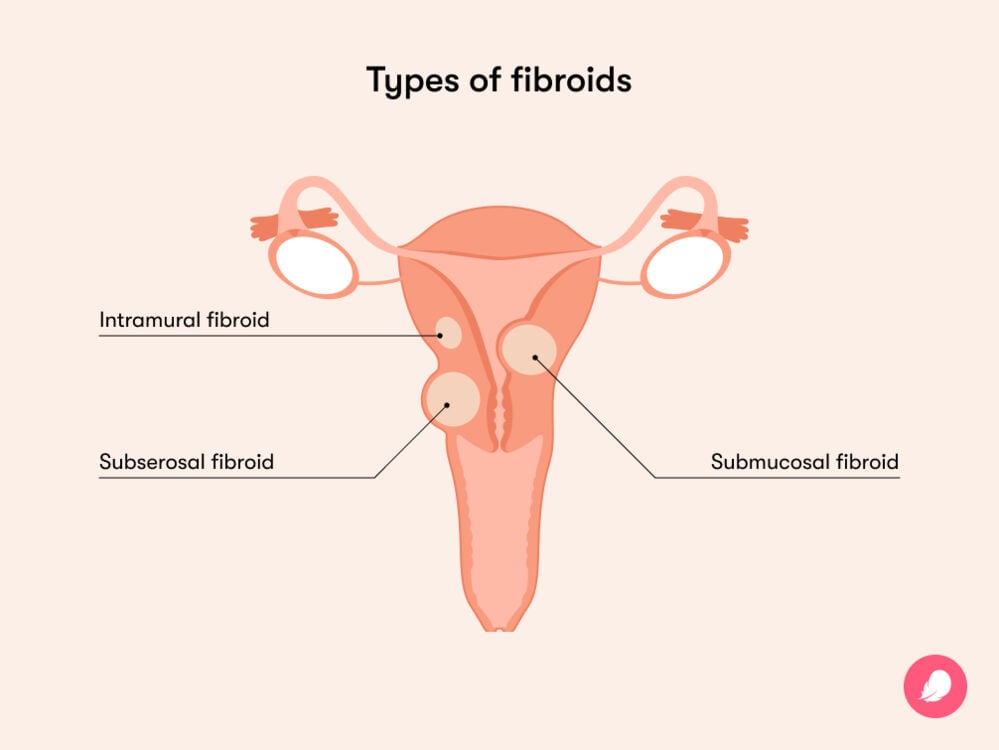

Fibroids can grow on their own or in a group, and they can vary in size. They might be as small as a seed, or they might grow to the size of a watermelon. There are three main types to know about:

- Intramural fibroids: The most common type, these grow in the muscle wall of the uterus.

- Subserosal fibroids: These attach to the outside of the uterus and can become quite large.

- Submucosal fibroids: These grow in the muscle layer inside the inner lining of the uterus.

Both subserosal and submucosal fibroids can also become pedunculated. This is a medical term for saying they have a stalk or a stem that attaches to the uterus, making them look a bit like mushrooms.

How common are fibroids?

If you’re diagnosed with fibroids, you’re certainly not alone. They’re incredibly common, with as many as 70% of women developing a fibroid at some point in their lifetime, usually when they’re of reproductive age (16 to 49 years old). And this number could be even higher, as those without symptoms might not even know they have them.

Do fibroids go away?

Fibroids can actually shrink by themselves over time, with one study suggesting that around 7% of fibroids will do so. While that’s not a high number, it’s good to know there’s a chance of it happening. And if you’re experiencing symptoms, these could ease off, too, once the fibroid shrinks.

Who gets fibroids?

Fibroids usually affect women, and people who have periods, of reproductive age (16 to 49 years old). This is because reproductive hormone levels — estrogen and progesterone — appear to play a role in their development, although researchers still aren’t entirely sure what causes fibroids.

Certain factors can increase your chances of having fibroids. These include:

- Genetics: A 2012 study found that having a family history of fibroids can increase your risk of developing them.

- Lifestyle: Being overweight or having high blood pressure can increase your risk of developing fibroids, as can being low on vitamin D.

- Periods: Starting your period before the age of 10 can increase your risk of developing fibroids.

- Ancestry: Studies have found that African American women are more likely to develop fibroids and have more severe symptoms.

If you have any of these risk factors and you’re concerned about fibroids, be sure to reach out to your health care provider for more advice.

Interestingly, the risk of developing fibroids decreases if you’ve been pregnant (it drops with each pregnancy) or used oral birth control (or injectable contraceptives) for an extended period of time. One study found that women who had used oral contraceptives for four to five years were 53% less likely to develop fibroids.

How do you know if you have fibroids?

If you don’t have any symptoms, then fibroids are often discovered during a routine pelvic exam or during an ultrasound. However, if you do experience any of the common symptoms below and think you might have fibroids, reach out to your health care provider. They can run tests, such as an ultrasound, to diagnose you and come up with a treatment plan to help you feel better.

What do fibroids feel like? And what are the symptoms?

There’s no one answer to this question, as experiences with fibroids vary from person to person. Most people won’t have any symptoms at all, but for those who do, the most common symptoms include:

- Heavy menstrual bleeding and longer periods

- Bleeding/spotting in between periods

- Menstrual cramps: One person in Flo’s Secret Chats forum said: “I recently found out that I have a large fibroid (14 cm) in the back lining of my uterus. I’ve experienced very painful cramps that just don’t go away.”

- Anemia, a condition that causes fatigue due to low iron which is caused by the heavy bleeding associated with fibroids

- Pain during sex: Another person in Secret Chats said: “[Fibroids are] restricting me so much; I haven’t had sex with my husband in over seven months as it’s too painful.”)

- Pain in the lower back or abdomen and pelvic pain (when fibroids press on surrounding organs)

- Needing to pee more often or having difficulty emptying your bladder: A person in Secret Chats said: “I have been experiencing bladder pain a lot, peeing a lot more, back pain, and pain in my stomach on and off.”

- Swelling in the uterus or abdomen (in the case of larger fibroids)

- Constipation

There’s no doubt that these symptoms can have a severe impact on your day-to-day life, so if you’re experiencing any of them, be sure to be kind to yourself. And you don’t just have to put up with them; there are treatment options and pain relief methods available, so always reach out to your doctor for advice.

Fibroid pain during pregnancy

If you’re pregnant, or planning to be, and have fibroid-related pain, then you might be wondering if it will get worse. Again, there’s no one experience that everyone will have, but what we do know is your hormone levels will rise during pregnancy. This can cause any fibroids you might have to grow in size. This could lead you to feel pain such as pelvic pain, stomach or lower back pain, or pain during sex.

This can sound scary, so be sure to discuss any concerns you might have with your health care provider. They will be able to offer advice while answering any questions you may have and develop a plan to closely monitor the fibroids during your pregnancy.

The good news is these fibroids might shrink or even go away altogether once your baby is here. In fact, one study of 157 women found that all fibroids had shrunk within six months of giving birth, while more than a third (37%) had disappeared on follow-up ultrasounds.

Speak to your doctor for advice on how to manage fibroid symptoms while you’re pregnant. They’re there to help and support you.

How to relieve fibroid pain

Numerous treatment options are available to help you relieve fibroid pain. Your first step is to speak to your doctor about what will work best for you, as treatment plans vary according to how many fibroids you have, their size, where they’re located, the symptoms you’re experiencing, and whether you’re planning to have a family.

After your consultation, your doctor may prescribe medications, including:

- Over-the-counter pain medication, such as ibuprofen: This could help to relieve the pain and discomfort you’re feeling.

- Hormonal birth control, such as the pill: Experts suggest this is particularly helpful in reducing heavy bleeding and painful menstrual cramps. If your fibroids aren’t on the inside of your uterus, then an intrauterine device that releases progestin could also help to reduce painful, heavy bleeding.

- Gonadotropin-releasing hormone agonists: These can help to shrink fibroids, although it’s worth noting that the effect is only temporary.

If your symptoms are particularly severe, your doctor might also recommend surgery to treat fibroid pain. This can sound scary; after all, choosing to have surgery is a big decision. You might have a number of questions and concerns or want more information about the different surgical options available. Always be sure to raise these with your health care provider, who will be able to offer you tailored advice and any other information you might need.

One of the concerns you might have could be related to your fertility, especially if you’re considering having children in the future. In this case, your doctor might recommend a myomectomy, which is a procedure to remove your fibroids from your uterus. Reassuringly, research has found that around 75% of women will go on to have a safe and healthy pregnancy after treating their fibroids in this way.

Alternatively, if you don’t want to preserve your fertility, you could opt to have a hysterectomy. This procedure will involve the removal of your uterus.

Your doctor will be able to talk you through the pros and cons of each option to help you make the best decision for you.

Should you get your fibroids removed?

Speak to your doctor if your fibroid symptoms are getting worse so that you can discuss all of the options available to you. Not everyone will need surgery to remove their fibroids, but it might be the best option for you.

It might also help to know that researchers are currently exploring new and less invasive treatment options for fibroids, although more research is needed to find out whether these options are effective.

More FAQs

Can I feel fibroids with my hands?

You can’t usually feel fibroids with your hands, although some people describe a hardness in their abdomen or a heaviness in their pelvis.

But you may find that your doctor can feel your fibroids with their hands during a pelvic exam, depending on their size and location. This is why a pelvic exam is often used to diagnose fibroids.

What happens if fibroids go untreated?

Not all fibroids will cause symptoms, so in some cases, it’s completely fine if they’re left alone. However, fibroids might lead to complications if left untreated. These can include severe pain, heavy periods, anemia, swelling in your abdomen or pelvic area, and, rarely, infertility.

The good news is that there are treatment options available to help (and they don’t always involve surgery), so speak to your doctor if you’re experiencing any symptoms of fibroids.

What is the earliest age for fibroids?

The earliest age for fibroids tends to be when women’s estrogen levels are high, so from about 16 years of age onward. However, fibroids are more common in your 30s and 40s.

Hey, I'm Anique

I started using Flo app to track my period and ovulation because we wanted to have a baby.

The Flo app helped me learn about my body and spot ovulation signs during our conception journey.

I vividly

remember the day

that we switched

Flo into

Pregnancy Mode — it was

such a special

moment.

Real stories, real results

Learn how the Flo app became an amazing cheerleader for us on our conception journey.

References

Barjon, Kyle, and Lyree N. Mikhail. “Uterine Leiomyomata.” StatPearls, StatPearls Publishing, 2023, www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK546680/.

Bochenska, Katarzyna, et al. “Fibroids and Urinary Symptoms Study (FUSS).” Female Pelvic Medicine and Reconstructive Surgery, vol. 27, no. 2, Feb. 2021, pp. e481–83, pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/33105342/.

Delli Carpini, Giovanni, et al. “The Association between Childbirth, Breastfeeding, and Uterine Fibroids: An Observational Study.” Scientific Reports, vol. 9, no. 10117, July 2019, www.nature.com/articles/s41598-019-46513-0.

Eggert, Stacey L., et al. “Genome-Wide Linkage and Association Analyses Implicate FASN in Predisposition to Uterine Leiomyomata.” American Journal of Human Genetics, vol. 91, no. 4, Oct. 2012, pp. 621–28, www.cell.com/ajhg/fulltext/S0002-9297(12)00421-1.

Eltoukhi, Heba M., et al. “The Health Disparities of Uterine Fibroid Tumors for African American Women: A Public Health Issue.” American Journal of Obstetrics and Gynecology, vol. 210, no. 3, Mar. 2014, pp. 194–99, www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC3874080/.

“Fibroids.” Johns Hopkins Medicine, www.hopkinsmedicine.org/health/conditions-and-diseases/uterine-fibroids. Accessed 15 Aug. 2023.

“Fibroid Locations.” Mayo Clinic, www.mayoclinic.org/diseases-conditions/uterine-fibroids/multimedia/fibroid-locations/img-20006761. Accessed 11 Jan. 2024.

“Fibroids: Overview.” NHS, www.nhs.uk/conditions/fibroids/. Accessed 15 Aug. 2023.

Khaw, Shen Chuen, et al. “Systematic Review of Pregnancy Outcomes after Fertility-Preserving Treatment of Uterine Fibroids.” Reproductive Biomedicine Online, vol. 40, no. 3, Mar. 2020, pp. 429–44, www.rbmojournal.com/article/S1472-6483(20)30003-1/fulltext.

Peddada, Shyamal D., et al. “Growth of Uterine Leiomyomata among Premenopausal Black and White Women.” Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America, vol. 105, no. 50, Dec. 2008, pp. 19887–92, www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC2604959/.

Saridogan, Ertan. “Surgical Treatment of Fibroids in Heavy Menstrual Bleeding.” Women’s Health, vol. 12, no. 1, Jan. 2016, pp. 53–62, www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC5779570/.

Shrestha, Rajesh, et al. “Fibroid Degeneration in a Postmenopausal Woman Presenting as an Acute Abdomen.” Journal of Community Hospital Internal Medicine Perspectives, vol. 5, no. 1, Feb. 2015, www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC4318819/.

Stewart, E. A., et al. “Epidemiology of Uterine Fibroids: A Systematic Review.” BJOG, vol. 124, no. 10, Sep. 2017, pp. 1501–12, pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/28296146/.

Uimari, Outi, et al. “Uterine Fibroids (Leiomyomata) and Heavy Menstrual Bleeding.” Frontiers in Reproductive Health, vol. 4, no. 818243, 4 Mar. 2022, www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC9580818/.

“Uterine Fibroids.” Cleveland Clinic, my.clevelandclinic.org/health/diseases/9130-uterine-fibroids. Accessed 20 Dec. 2023.

“Uterine Fibroids.” Mayo Clinic, 15 Sep. 2023, www.mayoclinic.org/diseases-conditions/uterine-fibroids/symptoms-causes/syc-20354288.

Mutch, David G., and Scott W. Biest. “Uterine Fibroids.” MSD Manual, May 2023, www.msdmanuals.com/en-gb/home/women-s-health-issues/fibroids/uterine-fibroids.

“Uterine Fibroids.” Office on Women’s Health, 19 Feb. 2021, www.womenshealth.gov/a-z-topics/uterine-fibroids.

“Uterine Fibroids.” The American College of Gynecologists and Obstetricians, July 2022, www.acog.org/womens-health/faqs/uterine-fibroids.

“What Are the Risk Factors for Uterine Fibroids?” Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development, www.nichd.nih.gov/health/topics/uterine/conditioninfo/people-affected. Accessed 20 Dec. 2023.

Zimmermann, Anne, et al. “Prevalence, Symptoms and Management of Uterine Fibroids: An International Internet-Based Survey of 21,746 Women.” BMC Women’s Health, vol. 12, no. 6, 26 Mar. 2012, www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC3342149/.