Changes in the cervix can lead to different Pap smear results, most of which are nothing to worry about. Keep reading to learn all about the different types of cervical changes, key symptoms to watch out for, treatment options, and how to prevent cervical cancer.

-

Tracking cycle

-

Getting pregnant

-

Pregnancy

-

Help Center

-

Flo for Partners

-

Anonymous Mode

-

Flo app reviews

-

Flo Premium New

-

Secret Chats New

-

Symptom Checker New

-

Your cycle

-

Health 360°

-

Getting pregnant

-

Pregnancy

-

Being a mom

-

LGBTQ+

-

Quizzes

-

Ovulation calculator

-

hCG calculator

-

Pregnancy test calculator

-

Menstrual cycle calculator

-

Period calculator

-

Implantation calculator

-

Pregnancy weeks to months calculator

-

Pregnancy due date calculator

-

IVF and FET due date calculator

-

Due date calculator by ultrasound

-

Medical Affairs

-

Science & Research

-

Pass It On Project New

-

Privacy Portal

-

Press Center

-

Flo Accuracy

-

Careers

-

Contact Us

Cervical Changes: Causes, Types, and Treatments

Every piece of content at Flo Health adheres to the highest editorial standards for language, style, and medical accuracy. To learn what we do to deliver the best health and lifestyle insights to you, check out our content review principles.

Cervical changes overview

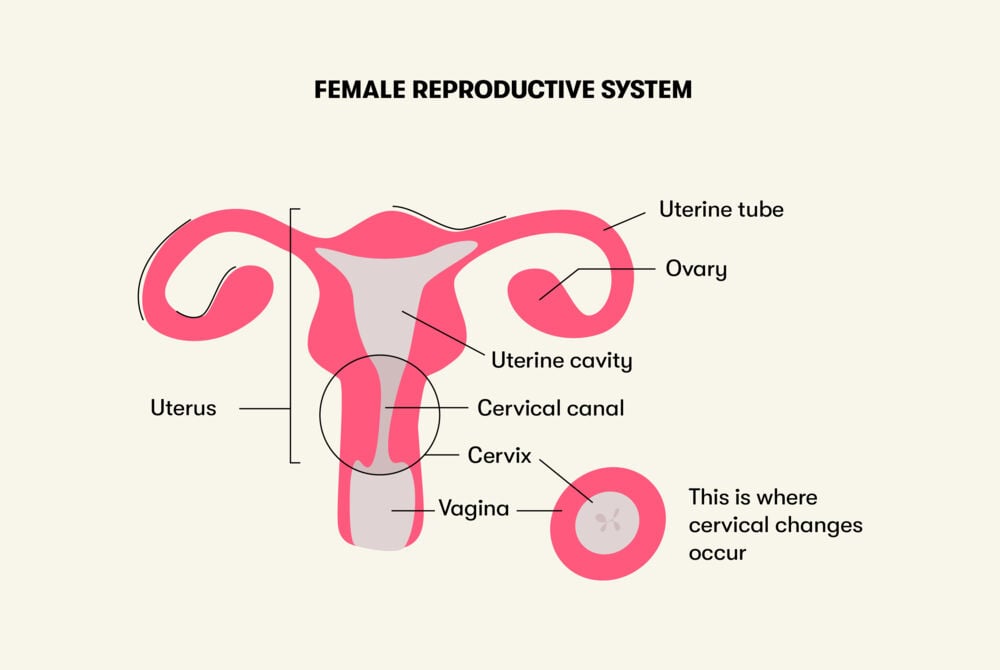

The cervix is a small, lower part of the uterus. It connects the vagina to the main part of the uterus.

When cervical cells are healthy, they are thin and flat. Lots of different things can cause changes in your cervical cells, such as an infection — HPV, for example — and hormonal changes that happen throughout life, like when you’re pregnant or going through menopause.

Most of the time, changes happen quite slowly in the cervix, and they can be detected by a Pap smear test. If a test shows abnormal results, it means that some of the cervical cells have taken on an abnormal shape.

An abnormal Pap test result is actually quite common and typically not as bad as it might sound. According to the Roswell Park Cancer Center, of the over 50 million Pap smears performed in the U.S. annually, around five percent have abnormal results.

If a screening shows that there’s been some changes in your cervix, there are lots of different potential causes for this, and it doesn’t automatically mean that you have cervical cancer. Your health care provider may recommend further testing or treatment to pinpoint exactly what’s going on.

Types of cervical changes

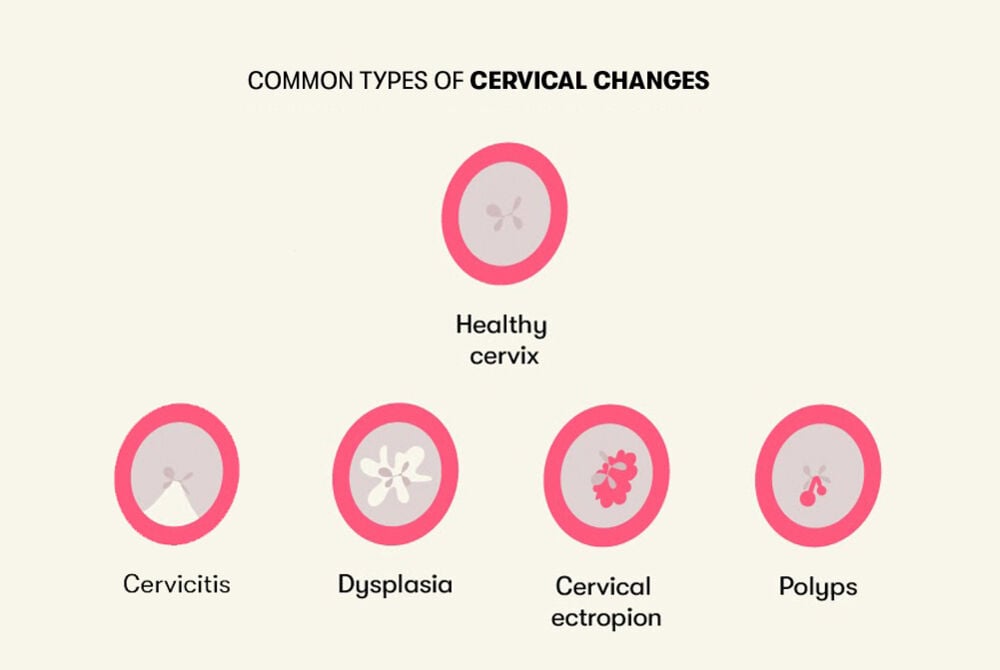

Each person’s cervix has distinctive features, and changes can happen at different seasons of life. Many of these changes are expected and totally harmless. Let’s explore the various types of changes to get a better understanding of what an abnormal Pap result can mean.

Cervical ectropion

Cervical ectropion — also called cervical eversion, ectropy, or erosion — occurs when the red, glandular cells lining the inside of the cervix grow on the outside. Essentially, the inside of the cervix turns outwards, due to a response to estrogen.

Between 17 and 50 percent of people will have cervical ectropion at some point in life. It’s especially common while going through puberty, during pregnancy, or when using contraceptives that contain estrogen — all of which cause hormonal changes in the body.

Take a quiz

Find out what you can do with our Health Assistant

Cervical polyps

Cervical polyps are cherry-red, reddish-purple, or grayish-white growths that develop on the cervix at the vaginal opening. They are usually completely harmless and often affect people over 20 who have given birth at least once. Only 1 per 1,000 cervical polyps are cancerous.

Health care providers aren’t entirely sure what causes polyps to form, but they seem to happen mostly when the cervix gets inflamed because of an unusual response to estrogen.

Cervicitis

Cervicitis happens when the cervix becomes inflamed. It’s usually caused by a sexually transmitted infection — such as chlamydia, gonorrhea, herpes — tuberculosis, or bacterial vaginosis (an overgrowth of bacteria which is normally in the vagina). Other potential causes of cervicitis include chemical exposure; an allergic reaction to spermicides, latex condoms, douches, or vaginal deodorants; and sensitivity to a device in the pelvic area, like an IUD or diaphragm.

Dysplasia (precancerous conditions)

Precancerous conditions of the cervix refer to abnormal cellular changes that can lead to cancer if left untreated. They’ll show up on Pap test results as cervical dysplasia, cervical intraepithelial neoplasia (CIN), or squamous intraepithelial lesion (SIL). If you find out that you have cervical dysplasia, this doesn’t mean that you have cervical cancer, but you may need to be monitored a bit more closely or have some cells removed to ensure it doesn’t become cancer.

Precancerous conditions occur in different stages:

- CIN1, mild cervical dysplasia, and low-grade SIL mean that there’s just a little bit of abnormal tissue. Most cases disappear all on their own without any treatment necessary. Your health care provider may recommend a follow-up appointment six months to a year later to see if there are any more changes.

- CIN2 or CIN3, moderate/severe cervical dysplasia, and high-grade SIL mean that there’s a larger portion of abnormal tissue on the cervix. These cells will need to be removed to prevent them from developing into cancer.

Between 250,000 and 1 million people in the U.S. are diagnosed with cervical dysplasia each year.

Signs and symptoms

Precancerous conditions of the cervix usually don’t cause symptoms, which is why it’s essential to get regular screenings. This is a critical step for preventing cervical cancer.

Many cancerous and harmless abnormalities on the cervix have the same symptoms — vaginal discharge, bleeding between periods or after sex, and pain during sex. Endometriosis and adenomyosis can also cause longer, heavy periods and severe menstrual cramps. For more info, take a look at the different treatment options for both endometriosis and adenomyosis. In rare cases, large cervical fibroids can make it difficult to pee.

If you experience any of these symptoms, see your health care provider for a checkup to find out what’s causing it.

Diagnosis and testing

To diagnose cervical changes, your health care provider will perform both a pelvic exam and a Pap smear. During a Pap test, your gynecologist will take a small sample of cells from the cervix so they can be examined under a microscope. The goal of the Pap test is to find cancerous or precancerous cells early on for prompt treatment.

An abnormal Pap smear or positive HPV result may signal that further testing is needed in order to see if there are cancerous or precancerous conditions on the cervix or if the results are due to an infection or harmless growth. Potential tests include colposcopy with or without biopsy (where a lighted magnifying instrument is used to examine the cervix and some cells may be removed), cone biopsy (removal of a cone-shaped piece of tissue from the cervix), and scraping of the cervical cells.

Treatment

Most benign cervical changes do not need treatment unless symptoms are getting in the way of daily life. Especially in younger people, abnormal cervical cells can return to normal by themselves. If you do end up needing treatment, there are several options depending on the particular condition causing the changes:

- Cervical polyps can be removed by a health care provider. Small cervical polyps that are under five millimeters in size do not need to be removed but should be looked into, while larger ones should be taken out to check for signs of cancer.

- Cervical ectropion can be treated by freezing, laser therapy, microwave tissue coagulation (using microwaves to direct heat at the area), or electrocautery (using heat to kill the abnormal cells).

- Cervicitis therapy depends on what caused the inflammation, and treatment may involve antibiotics or antiviral medicine.

High-grade precancerous cervical cells can be removed with a small scalpel (cold knife conization) or a thin wire loop (LEEP). Alternatively, they can be removed by freezing (cryotherapy) or laser therapy.

Takeaway

Many kinds of abnormal cell changes can take place in the cervix, and they’re often nothing to worry about. If you notice irregular vaginal bleeding or discharge or pain after sex, contact your health care provider to see what the cause may be. And remember to go for your regular Pap tests to protect your cervical health, detect any cellular changes, and treat them before they evolve into cancer.

Hey, I'm Anique

I started using Flo app to track my period and ovulation because we wanted to have a baby.

The Flo app helped me learn about my body and spot ovulation signs during our conception journey.

I vividly

remember the day

that we switched

Flo into

Pregnancy Mode — it was

such a special

moment.

Real stories, real results

Learn how the Flo app became an amazing cheerleader for us on our conception journey.