Around 85% of people will get HPV at some point in their lives, but what actually is it? Here’s the lowdown on HPV with advice from a Flo expert.

-

Tracking cycle

-

Getting pregnant

-

Pregnancy

-

Help Center

-

Flo for Partners

-

Anonymous Mode

-

Flo app reviews

-

Flo Premium New

-

Secret Chats New

-

Symptom Checker New

-

Your cycle

-

Health 360°

-

Getting pregnant

-

Pregnancy

-

Being a mom

-

LGBTQ+

-

Quizzes

-

Ovulation calculator

-

hCG calculator

-

Pregnancy test calculator

-

Menstrual cycle calculator

-

Period calculator

-

Implantation calculator

-

Pregnancy weeks to months calculator

-

Pregnancy due date calculator

-

IVF and FET due date calculator

-

Due date calculator by ultrasound

-

Medical Affairs

-

Science & Research

-

Pass It On Project New

-

Privacy Portal

-

Press Center

-

Flo Accuracy

-

Careers

-

Contact Us

Could you have HPV? Your questions answered

Every piece of content at Flo Health adheres to the highest editorial standards for language, style, and medical accuracy. To learn what we do to deliver the best health and lifestyle insights to you, check out our content review principles.

Imagine you were asked to name what you thought was the most common sexually transmitted infection (STI) in the world. You might say chlamydia, gonorrhea, or genital warts. However, the answer is human papillomavirus (HPV), which 85% of people will get at some point in their lives.

If you’re reading this and thinking you can’t remember HPV from your sex education syllabus, then fear not. HPV is simply the name for a group of viruses. Often, these viruses don’t cause issues and clear up on their own. In fact, lots of people don’t even know they have HPV because it’s usually symptomless. But sometimes, HPV can cause health issues.

Knowledge is power, so here’s the lowdown on an HPV infection — from what causes it to how to identify and prevent it.

Key takeaways

- Many people who have HPV don’t experience any symptoms. This might sound daunting, but there are ways to screen for HPV via a Pap smear and prevent it with vaccination.

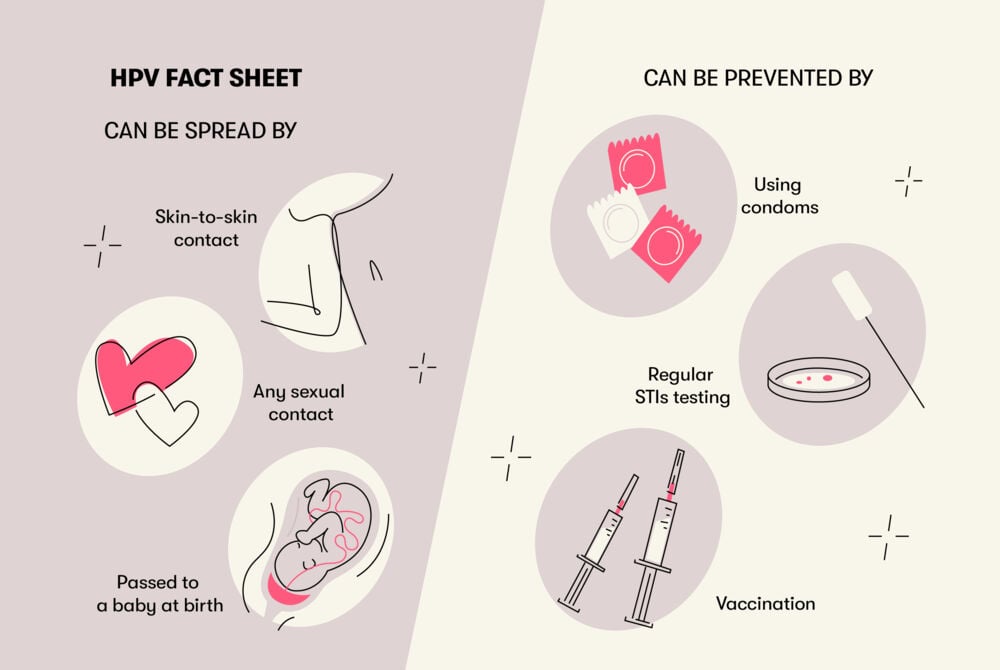

- It’s usually passed on through vaginal or anal sex but also spreads through close skin-to-skin contact during sex.

- There are more than 100 known strains of HPV, and different types can impact different parts of your body. Sometimes, sexually transmitted HPV infections can cause changes to the cells in your cervix and genital warts.

What does HPV look or feel like?

Human papillomavirus (HPV) is a common virus with over 100 strains. This means that different types of HPV can impact your body in different ways. Around 30 types of HPV can impact your vulva, vagina, or cervix in some way.

Both men and women can have HPV, but it’s tough to say what these viruses look and feel like because — as Dr. Renita White, obstetrician and gynecologist, Georgia Obstetrics and Gynecology, US — explains, “HPV does not have a look or feel.”

You can’t see or feel the human papillomavirus itself, but you might see or feel some of the symptoms of the conditions that you can end up with as a result of HPV infection. Confusing, right? Let’s go over what this means.

HPV symptoms in women and men

As we mentioned, there are more than 100 different types of HPV, and each one can have a different impact on your body. Here, we’re going to focus on the two most common sexual health-related HPV issues.

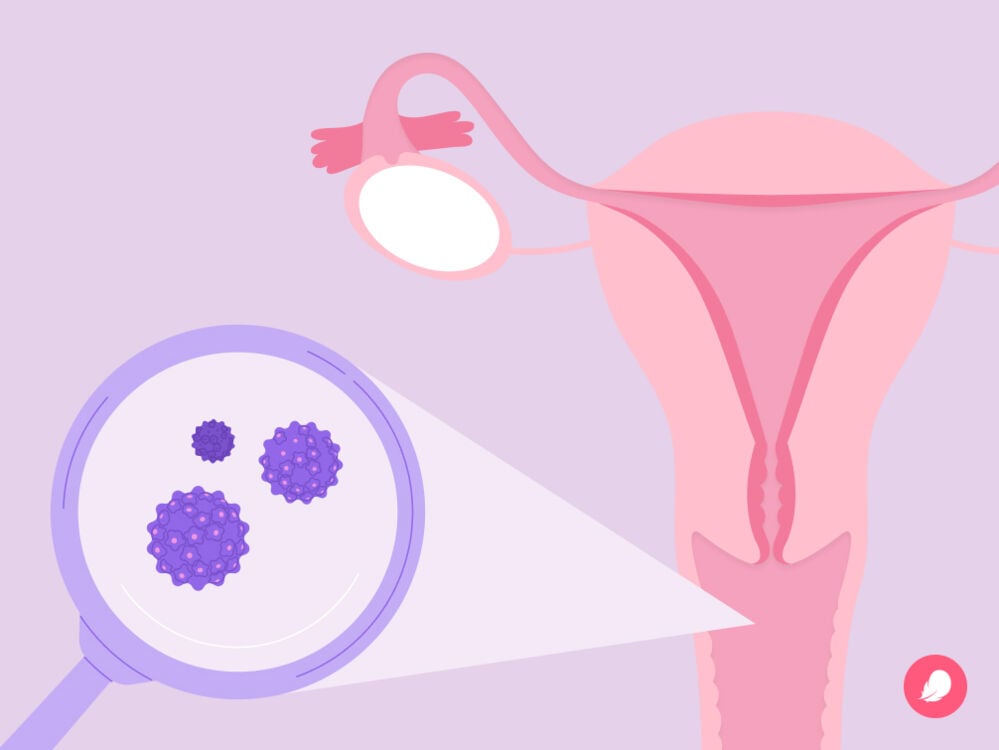

Changes to the cells on the surface of your cervix

You might be reading this after receiving an abnormal Pap smear result. This can be scary, but please know that getting an abnormal result is quite common. Cervical dysplasia affects between 250,000 and 1 million women in the United States every year, and it may not be anything to be too worried about. Understanding the link between HPV and the cells on the surface of your cervix may help to illustrate this.

A few strains of HPV (strains 16 and 18 specifically) can cause changes to the cells on the surface of your cervix. If you’re not entirely sure what or where your cervix is, it’s the tube-like muscle found at the top of your vagina, attaching it to your uterus.

When you have a Pap smear, your doctor takes a swab and swipes the surface of your cervix to check the cells. Some forms of HPV can cause abnormal cells to grow on the surface of your cervix. This is called cervical dysplasia.

Please know that not everyone who has HPV will experience cervical dysplasia, but if you do and it’s caught early, this condition is very treatable. It’s thought that around 250,000 to 1 million US cisgender women are diagnosed with cervical dysplasia each year — and your Pap smear is one of the best ways to detect it early. That’s why it’s so important to keep your screening up to date.

If it’s left undetected and untreated, cervical dysplasia can sometimes develop into cervical cancer. However, it’s so important to remember that not everyone who receives an abnormal Pap smear result or a cervical dysplasia diagnosis will ever get cervical cancer. In fact, the risk of an abnormal result indicating cancer is less than 1%.

Genital warts

As we’ve said, the different types of HPV can have very different effects on your body, and genital strains of HPV can cause the sexually transmitted infection (STI) genital warts.

If you think you might have genital warts, you might feel self-conscious or worried. Please know you’re not alone, and your doctor will be able to walk you through your symptoms and outline the best treatment option for you.

As their name would suggest, genital warts can be found around your vulva, vagina, or anus. They can look like small bumps that vary in size and be either raised, flat, or bumpy, like a cauliflower. Some people who have genital warts experience tingling, itching, or discomfort in the area where the warts are and bleeding after sex.

If you notice raised bumps or warts in your genital area, it’s really important that you reach out to your health care provider for a sexual health screening. They can examine you and may recommend a topical cream or treatment to soothe any of your symptoms.

It’s worth noting that other strains of HPV can cause different types of warts, including plantar and flat warts. Plantar warts can be found on the balls of your feet, while flat warts are small, raised lumps on the skin. The strains of HPV that cause these warts are different from those that can lead to either genital warts or changes to cells in the cervix.

Can you get HPV without warts?

Even if you get genital HPV, it’s very possible to have it without warts. In fact, 90% of people who get HPV will not develop genital warts.

Preventing the spread of HPV

As HPV can be spread through close skin-to-skin contact, it’s most commonly passed on through vaginal, anal, or oral sex. You can also catch it through close, intimate touching, such as using your fingers or mouth during sex.

“Because there is no way to test for HPV, many people don’t know they have it,” says Dr. White. “The main setting when people learn about a diagnosis of HPV is after a Pap smear.” However, there are things you can do to protect yourself and prevent the spread of HPV, including:

- Wearing barrier protection during sex

- Staying up to date with your Pap smear tests

- Having the HPV vaccine

Can you pass HPV back and forth?

Once you’ve cleared one particular strain of HPV, you’re not likely to get it again, as your immune system should protect you from getting the same type twice. This means you can’t pass HPV back and forth. However, you can still catch a different type of HPV in the future.

Can HPV come back once it has cleared?

It’s possible for HPV to be dormant in the body for months or even years. In rare cases, when a woman appears to have been reinfected with the same strain, experts still aren’t sure if it’s due to a new infection or an old one that has been dormant. As we mentioned above, even if you clear one type of HPV, it’s possible to get a different type at some point in your life.

How long can HPV be dormant?

There’s currently not enough evidence to know exactly how long HPV can be dormant, but we know it can be for years. “Because there is no routine way of testing for HPV, there is not much data on when someone contracts HPV or how long it remains in the body,” adds Dr. White.

What happens if HPV is left untreated

Currently, there’s no treatment for HPV itself. “Most cases of HPV clear within one to two years,” says Dr. White. “However, the strains that don’t clear in this time are more likely to cause health conditions.”

And there are things your doctor can do if your HPV turns into other conditions such as warts or cervical dysplasia. For example, sometimes genital warts can be treated with a cream, liquid, or ointment. Your doctor may also suggest physically removing the warts through laser surgery or by freezing them, for example.

Meanwhile, treatment for cervical dysplasia involves either carefully monitoring or removing any abnormal cells. Depending on your symptoms, your doctor will be able to recommend your best treatment options, so don’t hesitate to reach out to them.

Is HPV serious?

As we’ve seen, in the vast majority of cases, an HPV infection doesn’t cause any serious health problems and may go away by itself.

The most common way a doctor may notice you have HPV is through discovering cervical dysplasia after your Pap smear test. This is a condition where abnormal cells grow on the surface of your cervix. If you have cervical dysplasia, they may send you for a biopsy, where a small piece of tissue is removed from your cervix to be sent to a lab for testing.

It can be scary to find out you’ve got cervical dysplasia. But as we’ve seen, the condition only leads to cervical cancer in very rare cases. So, if you do receive an HPV and cervical dysplasia diagnosis, try not to worry. “Though HPV can increase the risk of cervical cancer, routine screening, treatment, and HPV vaccination have significantly decreased the chance of HPV-related cancers,” says Dr. White.

This is why it’s so important to keep up to date with your cervical screening tests and any necessary follow-up appointments. The process of HPV developing into cancer is very slow — it takes five to 10 years for HPV-infected cervical cells to develop into precancers (cervical dysplasia) and around 20 years to develop into cancer. This means your doctor has plenty of time to detect any precancerous cells as long as you keep up with your Pap tests.

Similarly, the HPV vaccine (or cervical cancer vaccine) can protect you against the strains of HPV that cause the most cancers. The World Health Organization (WHO) recommends that all girls aged 9 to 14 should get the vaccine as well as women between the ages of 15 to 21 who haven’t been vaccinated already. You may have already had it, depending on when and where you grew up. If you haven’t had the HPV vaccine and you’re older than 26, you’ll need to discuss whether it’s a good option for you with your doctor.

Take a quiz

Find out what you can do with our Health Assistant

What to do if you think you have HPV symptoms

If you think you have some of the symptoms associated with conditions that can develop from HPV (like warts), then it’s best to reach out to your doctor. They will talk through your symptoms with you and work out your best next step.

What to do if you think someone gave you HPV

“If you have sex with someone who tells you they have HPV, you were likely exposed, but there is no way to know, as there is currently no way to test for HPV other than in a Pap smear,” says Dr. White. “The best thing to do is to continue safe sex practices by limiting sexual partners and using condoms. And avoid sex with anyone having an active genital wart outbreak.”

While using condoms can help reduce the chances of passing HPV to others, condoms can’t eliminate the risk entirely, as HPV is spread by any close skin-to-skin contact.

What to do if you think you gave someone else HPV

As men can’t be tested for HPV, and there’s no way of knowing who gave the virus to whom, some doctors say that the question of whether to tell your partner (if they're male) you have HPV is not as straightforward as it is for other STIs. If you do want to talk to your partner about HPV but are not sure how to approach the conversation, check out our guide on how to tell someone they gave you an STI.

Ultimately, the best things you can do to prevent HPV-related health problems are to make sure you always attend your cervical screening tests and get the HPV vaccination. And if you find out for sure that you do have HPV, don’t beat yourself up about it. It doesn’t mean you’ve done anything wrong. With 85% of people getting an HPV infection in their lifetime, all it says about you is that you’re actually very normal.

Hey, I'm Anique

I started using Flo app to track my period and ovulation because we wanted to have a baby.

The Flo app helped me learn about my body and spot ovulation signs during our conception journey.

I vividly

remember the day

that we switched

Flo into

Pregnancy Mode — it was

such a special

moment.

Real stories, real results

Learn how the Flo app became an amazing cheerleader for us on our conception journey.

References

“Ask the Gynecologist: How Freaked out Should I Be about a Positive HPV Test?” Mayo Clinic Press, 7 Oct. 2022, mcpress.mayoclinic.org/women-health/how-freaked-out-should-i-be-about-a-positive-hpv-test.

“Basic Information about HPV and Cancer.” Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, www.cdc.gov/cancer/hpv/basic_info/index.htm. Accessed 26 Feb. 2024.

Brown, Darron R., and Bree Weaver. “Human Papillomavirus in Older Women: New Infection or Reactivation?” The Journal of Infectious Diseases, vol. 207, no. 2, 15 Jan. 2013, pp. 211–12, www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC3532821.

“Can HPV Come Back Once It Has Cleared?” MedicineNet,

www.medicinenet.com/can_hpv_come_back_once_it_has_cleared/article.htm. Accessed 26 Feb. 2024.

“Condom Effectiveness.” Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, www.cdc.gov/condomeffectiveness/index.html. Accessed 26 Feb. 2024.

“HPV and Cancer.” National Cancer Institute, 18 Oct. 2023, www.cancer.gov/about-cancer/causes-prevention/risk/infectious-agents/hpv-and-cancer.

“HPV Infection.” Mayo Clinic, 12 Oct. 2021, www.mayoclinic.org/diseases-conditions/hpv-infection/diagnosis-treatment/drc-20351602.

“HPV Test.” Mayo Clinic, 28 Oct. 2023, www.mayoclinic.org/tests-procedures/hpv-test/about/pac-20394355.

“Global HPV Vaccination.” Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, www.cdc.gov/globalhealth/immunization/diseases/hpv/index.html. Accessed 26 Feb. 2024.

“Human Papillomavirus (HPV) Treatment and Care.” Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, www.cdc.gov/std/hpv/treatment.htm. Accessed 26 Feb. 2024.

“Human Papillomavirus (HPV) Vaccination: What Everyone Should Know.” Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, www.cdc.gov/vaccines/vpd/hpv/public/index.html. Accessed 26 Feb. 2024.

“Human Papillomavirus (HPV) Infection.” Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, www.cdc.gov/std/treatment-guidelines/hpv.htm. Accessed 26 Feb. 2024.

“Human Papillomavirus (HPV) Vaccines.” The World Health Organization, www.who.int/teams/immunization-vaccines-and-biologicals/diseases/human-papillomavirus-vaccines-(HPV). Accessed 26 Feb. 2024.

IARC Working Group on the Evaluation of Carcinogenic Risks to Humans. “Human Papillomavirus (HPV) Infection.” IARC Monographs on the Evaluation of Carcinogenic Risks to Humans, No. 90. International Agency for Research on Cancer, 2007, www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK321770.

Leslie, Stephen W., et al. “Genital Warts.” StatPearls, StatPearls Publishing, Jan. 2023, www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK441884.

“Pap Test.” Johns Hopkins Medicine, www.hopkinsmedicine.org/health/treatment-tests-and-therapies/pap-test. Accessed 26 Feb. 2024.

“Plantar Warts.” Mayo Clinic, 7 Feb. 2024, www.mayoclinic.org/diseases-conditions/plantar-warts/symptoms-causes/syc-20352691.

“Reasons to Get HPV Vaccine.” Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, www.cdc.gov/hpv/parents/vaccine/six-reasons.html. Accessed 26 Feb. 2024.

“Genital HPV Infection – Basic Fact Sheet.” Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, www.cdc.gov/std/hpv/stdfact-hpv.htm. Accessed 26 Feb. 2024.

National Cancer Institute. Understanding Cervical Changes. A Health Guide. National Institutes of Health, Sep. 2021,

“What Is Recurrent HPV?” HPV Cancers Alliance, hpvca.org/what-is-recurrent-hpv. Accessed 26 Feb. 2024.

“Why Cervical Screening Is Important.” NHS, www.nhs.uk/conditions/cervical-screening/why-its-important. Accessed 26 Feb. 2024.