How clued up are you on the key differences between your vulva and vagina, and what exactly is going on in your breasts during puberty? With the help of some diagrams, two Flo experts explain everything you need to know about female anatomy.

-

Tracking cycle

-

Getting pregnant

-

Pregnancy

-

Help Center

-

Flo for Partners

-

Anonymous Mode

-

Flo app reviews

-

Flo Premium New

-

Secret Chats New

-

Symptom Checker New

-

Your cycle

-

Health 360°

-

Getting pregnant

-

Pregnancy

-

Being a mom

-

LGBTQ+

-

Quizzes

-

Ovulation calculator

-

hCG calculator

-

Pregnancy test calculator

-

Menstrual cycle calculator

-

Period calculator

-

Implantation calculator

-

Pregnancy weeks to months calculator

-

Pregnancy due date calculator

-

IVF and FET due date calculator

-

Due date calculator by ultrasound

-

Medical Affairs

-

Science & Research

-

Pass It On Project New

-

Privacy Portal

-

Press Center

-

Flo Accuracy

-

Careers

-

Contact Us

Vulva, vagina, and breasts: Parts of the female anatomy explained

Every piece of content at Flo Health adheres to the highest editorial standards for language, style, and medical accuracy. To learn what we do to deliver the best health and lifestyle insights to you, check out our content review principles.

Vagina, vulva … same thing, right? Both terms start with a V and refer to what’s between your legs, but they’re very different.

Although most people use the terms vulva and vagina interchangeably, it’s really important for our health and well-being to know how to correctly identify and label the different parts of our anatomy. And this includes your breasts. One of the key signs that you’ve hit puberty is your breasts will start to change shape, grow, and may become more sensitive. You can learn about all the ways your body changes during puberty using an app like Flo.

Changes in the way your body looks and feels can be hard to keep up with and wrap your head around. Here, two Flo medical board members explain everything you need to know about female anatomy — including the difference between the vulva and vagina and why there’s no such thing as “normal.”

Vagina vs. vulva: What’s the difference?

The vulva is the outer part of your genitals that you can see. The vagina is the inner, muscular canal that connects the vulva to the cervix (the small, donut-shaped muscle at the top of your vagina, connecting it to your uterus). A useful distinction to remember, right?

“We know that a lot of adult women don’t know [the] correct terminology or details about their genitalia,” says Dr. Beth Schwartz, assistant professor of obstetrics and gynecology and pediatrics, Pennsylvania, US. “I can’t think of anywhere else on the body where that is true. Imagine someone not knowing the difference between their eyebrow and eyeball. It’s kind of the same thing.”

Take a quiz

Find out what you can do with our Health Assistant

She’s got a point. But if you’re not sure what the difference between a vulva and a vagina is, then don’t worry. You’re not the only one. “I think it’s because we don’t talk about female genitals or sex enough,” explains Dr. Schwartz.

“We learn that ‘boys have penises and girls have vaginas’ but don’t talk about it more. And yet boys know the difference between the penis, scrotum, and testicles from a young age. Why should girls be different? We should absolutely call things by the correct names because they are made of different tissues and have different functions and problems.”

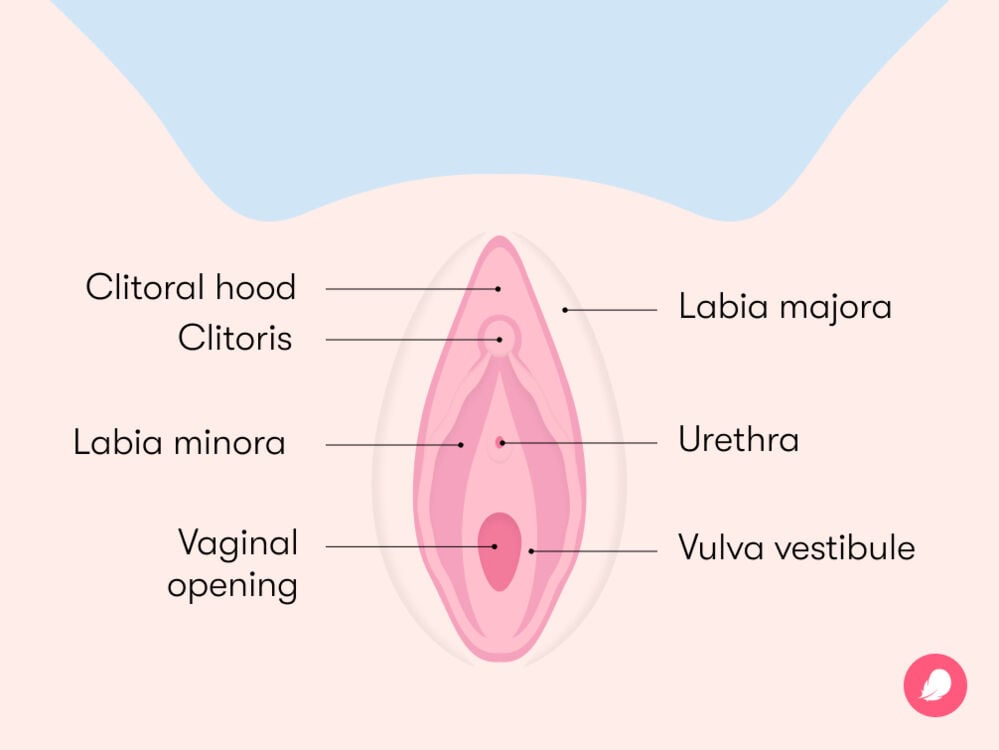

Parts of the external sexual anatomy

Let’s recap the facts: The vulva is the outer female sexual anatomy — all the parts you can see. The vulva is made up of two sets of lips (called labia majora and labia minora), the clitoris, the clitoral hood, the urethral opening, and the vaginal opening. Check out the diagram above to learn where each part is.

It’s totally fine to wonder if what you look like “down there” would be considered typical. Most of the time, we don’t have anything to compare it to. But the important thing to know about the vulva is that there is no such thing as perfect or ideal. Vulvas come in all shapes, sizes, and even colors (some are pinkish, while others can be more purple or brown).

A 2018 study of over 600 women found that the “average” vulva doesn’t exist because they’re all unique. The research found that the labia minora ranges hugely between 5 mm and 10 cm long, while the average labia majora ranges from 1.2 cm to 18 cm long.

“Know that you are totally normal,” says Dr. Barbara Levy, obstetrician and gynecologist, Washington, US. “Variations in size and shape of the vulva, just like variations in the size and shape of our noses, are absolutely expected and completely normal.”

Labia majora

The labia majora, sometimes referred to as the “outer lips,” are the fleshy folds where pubic hair grows. They’re the most external part of the vulva and come in all different sizes.

Labia minora

The labia minora are the “inner lips.” They look and feel different from the labia majora and tend to be softer, thinner, wet, and hairless.

“The labia, especially the labia minora, grow during puberty, the same way that breasts and hair do,” explains Dr. Schwartz.

“A lot of patients are concerned that their labia are too large or uncomfortable. They sometimes even request surgery to fix this. It is important for people to know that just like every other part of the body, labia come in all different shapes and sizes,” she says.

“Sometimes the labia majora are bigger and completely cover the labia minora. Sometimes the labia minora stick out beyond the labia majora. This is all normal.”

Dr. Levy agrees. “[The labia minora] are rarely the same on both sides, and they are not supposed to be. They do not need to be symmetrical. After all, it is hard enough for us to see these areas.”

Clitoris

The clitoris is the main area of sexual sensation in women and people with a vulva. From the outside, the clitoris looks like an oval-shaped nub that sits at the top of your labia minora. This visible part is called the “glans clitoris,” but it’s just the tip of the iceberg because the whole clitoris is much bigger inside, where you can’t see it.

The clitoris has an internal structure shaped like a wishbone that wraps around the vaginal canal (more on this below), but it’s not visible to the naked eye.

“The clitoris, our equivalent of the penis, seems tiny,” explains Dr. Levy. “It sits above the opening of the bladder (urethra) and is covered by a hood of tissue. Just as the penis enlarges with arousal, so does the clitoris.” The clitoris has the most nerve endings of any organ in the body — around 10,000 nerve fibers in total. This is what makes it so sensitive.

Clitoral hood

The clitoral hood is a flexible fold of skin covering the glans clitoris (the small part of the clitoris you can see.) Just like the clitoris, the clitoral hood can come in different sizes — some people have a bigger, fleshier clitoral hood, while others have a tighter or thinner one.

The clitoral hood is there to protect your clitoris, which is highly sensitive, from friction or irritation. When you’re sexually aroused, your clitoris swells up and the clitoral hood pulls back to expose the glans clitoris. The clitoral hood is the equivalent of the foreskin on a penis. Who knew there were quite so many similarities between male and female genitalia?

Urethral opening

The urethral opening is the hole that connects the urethra to the vulva. “Women urinate from the urethra, which is the tube that delivers urine from the bladder to the outside,” explains Dr. Schwartz. “[The urethral opening] is a small opening within the vulva but separate from and just above the vagina. Many adult women don’t know this.”

So you have two holes, not one. Your urethra is just above your vaginal opening and below your clitoris.

Vaginal opening

To finish off the parts of your intimate anatomy that you can see from the outside, you have your vaginal opening. The area surrounding your vaginal opening and your urethra is called the vaginal vestibule.

When you give birth, the baby comes out of your vaginal opening, and it’s where your period blood leaves your body. You’ll be able to see it, between your labia minora, below your clitoris. See the diagram above for a little bit of a roadmap.

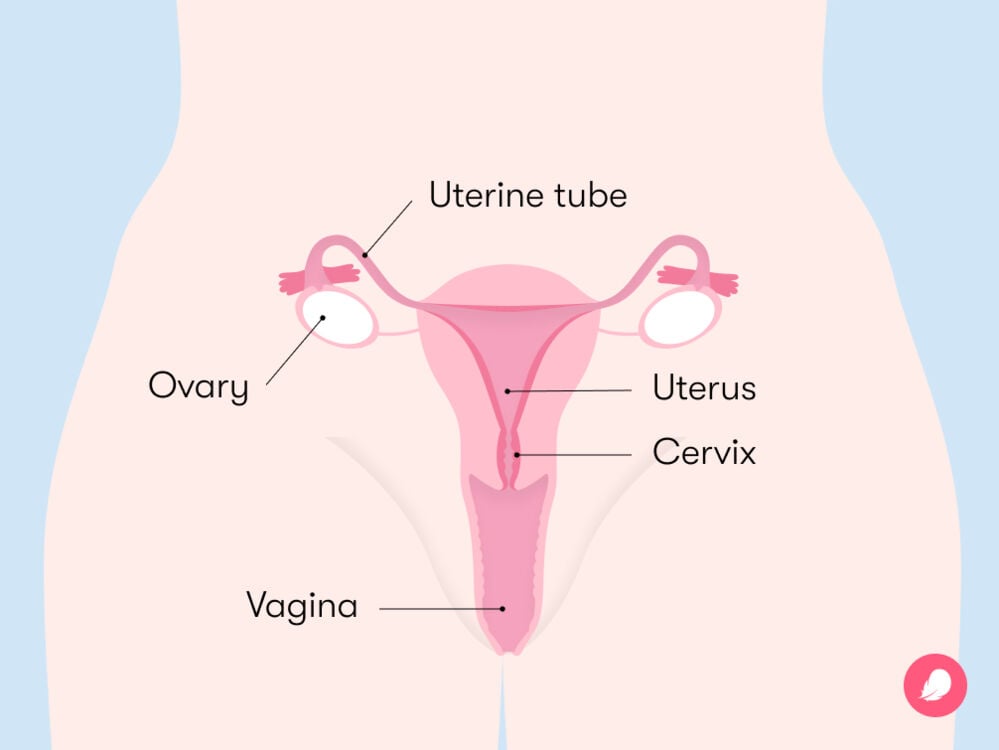

Parts of the female internal sexual anatomy

So now that we’ve explored the vulva, let’s have a look inside. Female sexual anatomy doesn’t stop at what you see from the outside.

Vagina

The vagina is the inner muscular canal that connects the vulva to the cervix. “It’s how menstrual blood (periods) come out, where tampons go, and the birth canal that babies are delivered through,” says Dr. Schwartz.

The walls of your vagina also make discharge. You might have seen it in your underwear. Typically, it shouldn’t be strong smelling and may appear to be milky, creamy, watery, or sticky. Its consistency might change throughout your cycle, and this is totally normal. This is due to changes in your hormones. Don’t forget — you can track your cycle using an app like Flo.

Here’s a useful fact to remember: You don’t have to clean or wash your vagina, despite what you may have been told. “The vagina is self-cleaning,” says Dr. Schwartz. “The use of soap or any feminine hygiene products inside the vagina can actually cause an infection.”

You might have heard about pH in your chemistry classes, and it’s about to come in handy. The vagina has a delicate balance of good bacteria and a natural pH of 3.8 to 5, making it slightly acidic. Heavily scented soaps and hygiene products can upset the balance of bacteria in your vagina leading to infections like bacterial vaginosis.

"Any major change in discharge or associated itching, irritation, or odor should be checked out by a doctor,” says Dr. Schwartz. “That said, the vagina is supposed to smell like a vagina, not a spring meadow.” Noted.

Cervix

Your cervix is round in shape with a hole in the middle. It acts as a barrier to your uterus, preventing any bacteria from getting inside. It’s also the reason why it’s impossible to “lose” something inside your vagina. So if you’ve ever wondered if a tampon can get lost inside you, rest assured it won’t get past your cervix.

“The cervix is the bottom part of the uterus,” explains Dr. Schwartz. “[You might have] heard of it dilating (stretching) during labor. It is the part that is swabbed for a pap test.”

Uterus

The uterus is the hollow, muscular organ where a fetus grows during pregnancy. It’s also where your period blood originates from. You might have heard your biology teacher call it a womb.

During your menstrual cycle, the inner lining of the uterus (called the endometrium) grows and becomes thicker to prepare for a possible pregnancy. If you don’t get pregnant after an egg is released from one of your ovaries, that lining sheds and leaves your body via the cervix and vagina. This is your period.

The uterus contracts to expel the old lining, and that’s what can cause period cramps. While it can be a drag, the cramps you might experience are part of a really important process. You can learn more about your cycle and premenstrual syndrome (PMS) using an app like Flo.

Ovaries

The ovaries are small, oval glands located on both sides of your uterus. After puberty, the ovaries start making hormones called estrogen and progesterone. These hormones control your cycle from when you start your period to when your ovaries release an egg.

The ovaries are also responsible for storing and maturing eggs. Cool fact: It’s thought that you’re born with all the eggs you’ll ever have. On average, that’s around 1-2 million eggs.

Every month, one of your ovaries releases an egg through the uterine tube and into the uterus. This is known as ovulation. If fertilized by a sperm, this egg will become an embryo and start a pregnancy. If it’s not fertilized, the egg will break down after 24 hours.

Fallopian tubes (also known as uterine tubes)

The fallopian or uterine tubes are two tubes connected to your uterus that transport eggs from the ovaries to the uterus.

Here’s another fun fact: the uterine tubes aren’t actually attached to the ovaries. An egg moves from the ovary to the uterine tube via small, finger-shaped branches called fimbriae, found at the end of the uterine tubes. You can see these in the diagram above.

Breasts in female anatomy

Your vulva isn’t the only thing that changes as you transition into puberty. In fact, one of the earliest signs that you’ve started puberty and you might expect your first period is your breasts and nipples grow, change shape, and change color.

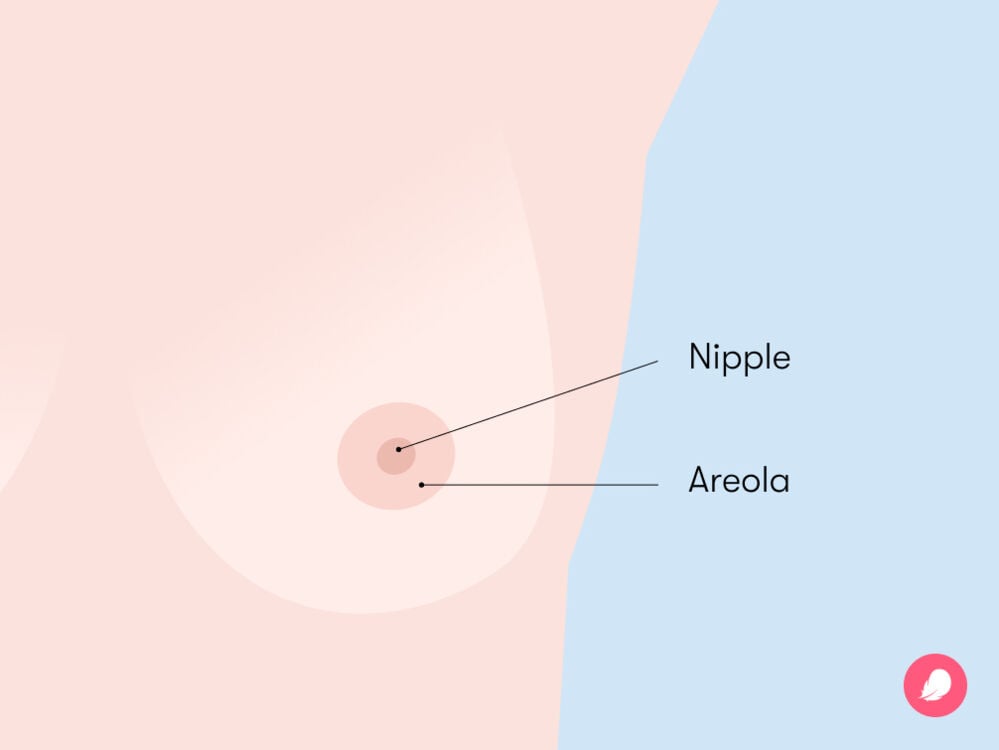

External breast anatomy

Like your vulva and vagina, there are parts of your breast anatomy that you can see and parts that you can’t. Boobs can come in all shapes and sizes, and there’s no such thing as normal or perfect boobs. They’re all wonderful. And knowing what’s typical for you is really important so you can spot any changes.

Your external breast anatomy is made up of:

- Areolae: This is the skin around your nipple that is typically darker in color than your skin tone.

- Nipple: Your nipples are in the center of your areolae and have around nine milk ducts each. They’re also covered in nerve endings, meaning your nipples might be sensitive to touch or temperature changes.

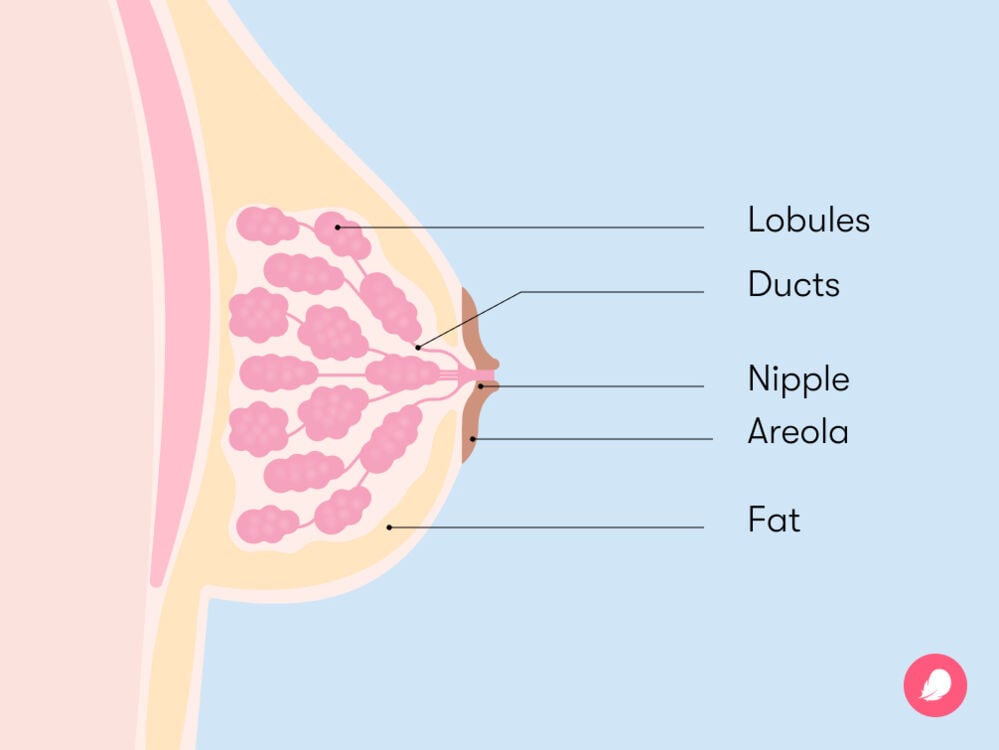

Internal breast anatomy

Internally, your breasts are split into a number of sections that all branch out from your nipples. If this sounds complicated, don’t worry; the diagram should clear this up.

Internally, your breasts are made up of:

- Lobes and lobules: Lobes are the medical name for sections that each breast is split into. You have around 15 to 20 lobes in each breast. Lobules are smaller sections within these lobes that have glands at the end. If you’re breastfeeding, this is where the milk is produced.

- Mammary (or milk) ducts: Your mammary ducts are small tubes that carry milk produced in your lobules to the milk ducts in your nipples.

- Breast tissue: This is fatty tissue that surrounds the lobules and determines the size of your boobs.

- Blood vessels: You have a network of blood vessels in your boobs to ensure that you get enough oxygen and nutrients to the tissue.

Female anatomy: The takeaway

Knowing your body inside and out may help you break down some of the stigmas that are attached to the vulva, vagina, and boobs. If this has highlighted anything, it’s that there’s no such thing as ideal or perfect, and the most important thing is that you’re healthy and happy.

Being able to identify and label different parts of your anatomy might also help you spot when something isn’t quite right so you can accurately describe the problem to someone you trust and your healthcare provider.

Most people use the words “vagina” and “vulva” interchangeably, but there is a clear difference, and it’s about time more of us understood it. The vulva is the outer part of female sexual anatomy, made up of the labia majora, labia minora, clitoris, and vaginal opening. The vagina is the inner canal that connects the vulva to the cervix.

“Wouldn’t it be awful if we searched for information about our nose, only to find out later that what we really needed was information about our sinuses? That’s the story with our parts down there,” explains Dr. Levy. “To be able to troubleshoot symptoms and problems, we first need to know which area we’re talking about."

Hey, I'm Anique

I started using Flo app to track my period and ovulation because we wanted to have a baby.

The Flo app helped me learn about my body and spot ovulation signs during our conception journey.

I vividly

remember the day

that we switched

Flo into

Pregnancy Mode — it was

such a special

moment.

Real stories, real results

Learn how the Flo app became an amazing cheerleader for us on our conception journey.

References

“Breast Anatomy.” Cleveland Clinic, my.clevelandclinic.org/health/articles/8330-breast-anatomy. Accessed 27 Oct. 2022.

“Cervix.” Cleveland Clinic, my.clevelandclinic.org/health/body/23279-cervix. Accessed 27 Oct. 2022.

“Clitoris.” Cleveland Clinic, my.clevelandclinic.org/health/body/22823-clitoris. Accessed 27 Oct. 2022.

“Early or Delayed Puberty.” NHS, www.nhs.uk/conditions/early-or-delayed-puberty/. Accessed 27 Oct. 2022.

“Female Age-Related Fertility Decline.” American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists (ACOG), www.acog.org/clinical/clinical-guidance/committee-opinion/articles/2014/03/female-age-related-fertility-decline. Accessed 7 March 2023.

Kreklau, A., et al. “Measurements of a ‘Normal Vulva’ in Women Aged 15–84: A Cross-Sectional Prospective Single-Centre Study.” BJOG: An International Journal of Obstetrics and Gynaecology, vol. 125, no. 13, Dec. 2018, pp. 1656–61.

Lin, Yen-Pin, et al. “Vaginal pH Value for Clinical Diagnosis and Treatment of Common Vaginitis.” Diagnostics, vol. 11, no. 11, Oct. 2021, doi.org/10.3390/diagnostics11111996.

Nguyen, John D., and Hieu Duong. “Anatomy, Abdomen and Pelvis, Female External Genitalia.” StatPearls, StatPearls Publishing, 2022.

“Overview of the Male Anatomy.” John Hopkins Medicine, 19 Nov. 2019, www.hopkinsmedicine.org/health/wellness-and-prevention/overview-of-the-male-anatomy.

“Vagina: What’s Typical, What’s Not.” Mayo Clinic, 18 Jan. 2022, www.mayoclinic.org/healthy-lifestyle/womens-health/in-depth/vagina/art-20046562.

“Vulva.” Mayo Clinic, 25 Apr. 2020, www.mayoclinic.org/vulva/img-20005974.

“Vulvar Care.” Cleveland Clinic, my.clevelandclinic.org/health/articles/4976-vulvar-care. Accessed 27 Oct. 2022.