Want to know more about GSM and what it really means? With help from a Flo expert we explain it in simple terms — plus ways to track symptoms.

-

Tracking cycle

-

Getting pregnant

-

Pregnancy

-

Help Center

-

Flo for Partners

-

Anonymous Mode

-

Flo app reviews

-

Flo Premium New

-

Secret Chats New

-

Symptom Checker New

-

Your cycle

-

Health 360°

-

Getting pregnant

-

Pregnancy

-

Being a mom

-

LGBTQ+

-

Quizzes

-

Ovulation calculator

-

hCG calculator

-

Pregnancy test calculator

-

Menstrual cycle calculator

-

Period calculator

-

Implantation calculator

-

Pregnancy weeks to months calculator

-

Pregnancy due date calculator

-

IVF and FET due date calculator

-

Due date calculator by ultrasound

-

Medical Affairs

-

Science & Research

-

Pass It On Project New

-

Privacy Portal

-

Press Center

-

Flo Accuracy

-

Careers

-

Contact Us

Genitourinary syndrome of menopause: Let’s break it down

Every piece of content at Flo Health adheres to the highest editorial standards for language, style, and medical accuracy. To learn what we do to deliver the best health and lifestyle insights to you, check out our content review principles.

Does something feel like it’s not right with your vulva or vagina, and you’re not sure of the cause? Perhaps it feels dry and itchy, sex is uncomfortable, or you constantly need to pee lately?

There’s a chance a yeast infection or a urinary tract infection (UTI) could be the cause. But if you have one or more of these symptoms — and you’re somewhere between your late 30s and your 50s — there may be something else going on. It could be genitourinary syndrome of menopause (GSM), a cluster of issues that can affect women around the time of menopause (and can continue after).

Menopause is a process that anyone born with a female reproductive system goes through. Not everyone finds this a tricky time, but the run-up to menopause — called perimenopause — can include some difficult symptoms. Some of the better-known ones include hot flashes and brain fog, but vaginal dryness, needing to pee more, and painful sex can also come as part of it.

When we’re faced with symptoms like vaginal dryness and painful sex, we don’t always realize perimenopause could be the reason. But GSM is an ongoing condition that can affect your quality of life and potentially your relationships, so it’s a good idea to get some help if it’s bothering you. With the right treatment, GSM symptoms can become manageable.

In the meantime, we share everything you need to know about genitourinary syndrome of menopause, from why it happens to how it can be treated.

Key takeaways: Genitourinary syndrome of menopause

- Around 15% of women experience symptoms of GSM before menopause, and as many as 84% of women have it postmenopause.

- Falling estrogen levels are thought to be the biggest cause of GSM symptoms.

- The name GSM is given to symptoms affecting multiple parts of your body, including your vagina, labia, urethra, and bladder.

- GSM can get worse without treatment, but with the right care, it can be managed. So it’s always a good idea to speak to your doctor if you think you have it.

- Hormone therapy (previously known as hormone replacement therapy or HRT) has been found to ease symptoms for many women, but it’s not right for everyone, so chat with your doctor if you’d like to know more.

What is genitourinary syndrome of menopause (GSM)?

Genitourinary syndrome of menopause (GSM) is an umbrella term used to describe a number of vulvovaginal (which means all things vulva and vagina) and urinary symptoms. Another name for it is vaginal atrophy, and it’s essentially a condition that causes the lining of your vagina to become drier, thinner, and more fragile. As a result, it can lead to itching, burning, pain during sex, and other symptoms.

But the term vaginal atrophy has fallen out of favor in recent years — which is unsurprising given that atrophy literally means “wasting away.” Following a 21st-century upgrade, experts now use the term genitourinary syndrome of menopause “to more accurately describe the constellation of symptoms that occur in midlife,” says Dr. Sameena Rahman, clinical assistant professor of obstetrics and gynecology, Northwestern Feinberg School of Medicine, Illinois, US.

GSM symptoms are most common when you’re postmenopausal (meaning you no longer have periods and you can’t get pregnant by having sex). In fact, it’s thought that as many as 84% of postmenopausal women go on to develop GSM. But occasionally, the first signs of GSM can start during perimenopause, which is your transition through menopause. It covers the years leading up to menopause and the 12 months after, at which point you can be sure you’ve had your final period (this usually happens between the ages of 45 and 55).

According to a 2019 review, vaginal dryness is one of the most common symptoms of genitourinary syndrome of menopause, but it’s not the only one. Other symptoms of GSM include:

- Burning and/or itching in your vagina or on your vulva

- Pain during sex

- Spotting or bleeding during sex

- Difficulty feeling aroused

- Difficulty having orgasms

- Frequent UTIs

- Being unable to hold in your pee (incontinence)

- An increased urge to pee

GSM doesn’t typically settle with time, which means it’s likely to continue or possibly get worse without help. But with the right care, you can ease your symptoms, so schedule an appointment with your doctor, and they’ll be able to share some advice on how to treat it.

Take a quiz

Find out what you can do with our Health Assistant

What causes genitourinary syndrome of menopause (GSM)?

Just like other more widely known perimenopause symptoms, such as hot flashes and joint pain, GSM can be linked to changing hormone levels.

As you approach menopause, your hormone levels (estrogen in particular) can become unpredictable before eventually dropping for good. It’s this hormonal disruption that causes the different symptoms that can happen during perimenopause and beyond. We have hormone receptors all over our bodies, which is why menopausal symptoms can affect you anywhere from head to toe.

Vaginal GSM symptoms happen because estrogen plays an important role. “The vagina needs estrogen to stay healthy,” says Dr. Rahman. When you have lower estrogen levels, your vaginal walls become thinner, and there’s less blood flow to the area, which means you produce less natural lubrication.

GSM can also include an increased need to pee and difficulty holding it in, and these urinary symptoms can also be due to a change in hormones. “Without estrogen, urinary symptoms such as pain, frequency, and urgency increase,” explains Dr. Rahman. Some women also notice more urinary tract infections (UTIs) during this time. That’s because “the urethra becomes enlarged,” explains Dr. Rahman, meaning there’s more chance of bacteria entering your system.

If you’ve noticed your desire for sex has dropped, that may also be related to GSM, thanks to a menopausal change in hormones. “The lack of androgens [a type of sex hormone] leads to shrinking of the vulva, including labia minora and clitoris, which can impact sexual function, arousal, and orgasms,” says Dr. Rahman. For some people, sex might become painful due to the changes in their vagina, and it can be common to avoid sex because you’re anticipating pain.

If your sex drive has taken a hit, or you’re bothered by changes to your vagina or your bathroom habits, don’t lose hope. There are lots of things you can do to feel like yourself again. “This should be treated and not ignored,” says Dr. Rahman. “There are solutions that will improve your quality of life and sexual function.” Chat with your doctor to figure out your next step.

How is GSM diagnosed?

GSM is very common after menopause, and in some cases, it can start in perimenopause. But the assumption that it’s a natural part of aging — combined with many people feeling too embarrassed to talk openly about it — means it’s often underdiagnosed. However, it’s important to seek out help if you think you’ve got GSM because it’ll only get better with the right care.

In order to diagnose GSM, your doctor will probably do a pelvic exam to see if they can spot any common signs. They’ll be looking for things like:

- A vagina that’s shortened or narrowed

- Dryness, redness, or swelling in the area

- A loss of stretchiness

- Discoloration of your vagina (usually whitish)

- Small cuts near your vaginal opening

- A decrease in the size of your labia

A pelvic exam will usually be enough to diagnose GSM on its own, but your doctor can always do further tests (like urine samples, ultrasound scans, Pap tests, and more) if they’re unsure.

What’s the best treatment for GSM?

Everyone is unique, and no two people have the exact same symptoms, meaning there isn’t a one-size-fits-all approach to managing GSM. Your doctor will be able to talk you through all the options and help you figure out the right path to take. To begin with, you might need to experiment with different methods until you find the one that works for you. Treatment options for GSM include:

- Vaginal moisturizers and lubricants: Using lube during sex and a daily moisturizer won’t address the cause of your GSM symptoms, but they should help to ease your discomfort. “There are what I call [make-do solutions] that would include lubricants before sex or vaginal moisturizers like hyaluronic acid-based treatments,” says Dr. Rahman.

- Local estrogen therapy: Hormone therapy (HT) can help with GSM symptoms by supplying you with the key sex hormones you produce less of during perimenopause. But it isn’t for everyone, so talk to your doctor about the pros and cons. If you have GSM, vaginal estrogen applied locally to the area can help ease symptoms without increasing levels of estrogen in your bloodstream. “There are many forms of vaginal estrogen — in the form of a pill, cream, or insert,” says Dr. Rahman. Alternatively, taking oral medication such as ospemifene, which provides estrogen locally to the vagina, can be a good option for women who do not like using vaginal products.

- Dehydroepiandrosterone (DHEA): DHEA is a hormone that your body naturally produces, but levels start to drop from early adulthood onward. It’s thought that taking a synthetic version as a tablet, capsule, powder, cream, or gel may improve vaginal dryness in postmenopausal women, but more research is needed into this as a treatment option for GSM.

- Pelvic floor therapy: Your pelvic floor is a group of muscles and ligaments that support your bladder, vagina, and bowel, and they can weaken with age. For that reason, it’s always a good idea to do your Kegel exercises, and it may prove especially useful if you have GSM. “Pelvic floor therapy is important for the [stiff] muscles that develop from lack of oxygen and blood flow to the vagina,” says Dr. Rahman. Chat with your doctor if you’d like to start practicing pelvic floor exercises.

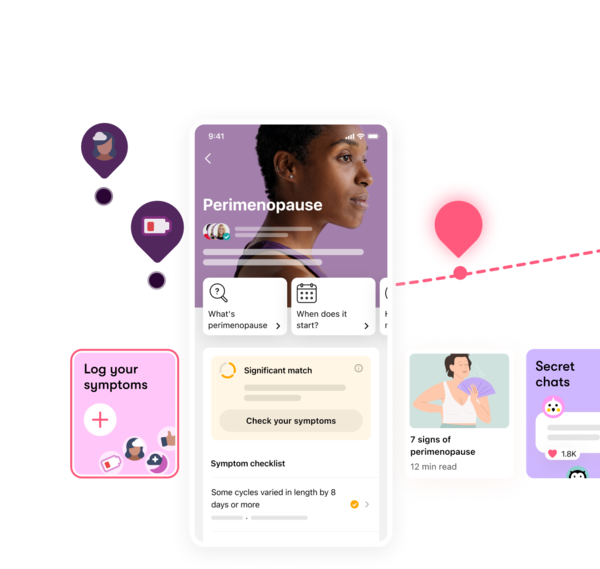

If your periods have started to change and you think you might be entering perimenopause, Flo’s period tracking app can help you keep tabs on your cycle. You can also log menopausal symptoms such as vaginal dryness and hot flashes, which may be useful if you end up seeing a doctor about what you’re experiencing. Plus, chatting with like-minded people in a similar situation may help you to feel more supported as you go through perimenopause. You can do exactly that in Flo’s safe community space, Secret Chats. Download the app to get involved in these conversations and keep note of your symptoms, cycles, and more.

Frequently asked questions about genitourinary syndrome of menopause

What are some symptoms of genitourinary syndrome of menopause?

The most common symptoms of GSM include vaginal dryness, dyspareunia (painful sex), vaginal irritation, itching, tenderness, bleeding, or spotting during sex. Also, UTIs, incontinence, or a frequent urge to urinate are known to be symptoms of genitourinary syndrome of menopause.

What is a genitourinary syndrome of menopause diagnosis?

“It is diagnosed by history and physical exam,” says Dr. Rahman. In some cases, your doctor may also ask you to do a urine test to see if you have urinary symptoms. They may also suggest doing an acid balance test, which involves taking a sample of vaginal fluids or placing a paper indicator strip in your vagina to test its acid balance.

Hey, I'm Anique

I started using Flo app to track my period and ovulation because we wanted to have a baby.

The Flo app helped me learn about my body and spot ovulation signs during our conception journey.

I vividly

remember the day

that we switched

Flo into

Pregnancy Mode — it was

such a special

moment.

Real stories, real results

Learn how the Flo app became an amazing cheerleader for us on our conception journey.

References

Abraham, Cynthia. “Experiencing Vaginal Dryness? Here’s What You Need to Know.” The American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists, Oct. 2020, www.acog.org/womens-health/experts-and-stories/the-latest/experiencing-vaginal-dryness-heres-what-you-need-to-know.

Academic Committee of the Korean Society of Menopause, et al. “The 2020 Menopausal Hormone Therapy Guidelines.” Journal of Menopausal Medicine, vol. 26, no. 2, Aug. 2020, pp. 69–98, doi:10.6118/jmm.20000.

Alizadeh, Ameneh, and Farnaz Farnam. “Coping with Dyspareunia, the Importance of Inter and Intrapersonal Context on Women’s Sexual Distress: A Population-Based Study.” Reproductive Health, vol. 18, no. 1, July 2021, p. 161, doi:10.1186/s12978-021-01206-8.

“Androgens.” Cleveland Clinic, my.clevelandclinic.org/health/articles/22002-androgens. Accessed 11 June 2024.

Angelou, Kyveli, et al. “The Genitourinary Syndrome of Menopause: An Overview of the Recent Data.” Cureus, vol. 12, no. 4, Apr. 2020, doi:10.7759/cureus.7586.

Bleibel, Belal, and Hao Nguyen. “Vaginal Atrophy.” StatPearls, StatPearls Publishing, 2023, europepmc.org/article/med/32644723

Chen, Peng, et al. “Role of Estrogen Receptors in Health and Disease.” Frontiers in Endocrinology, vol. 13, Aug. 2022, doi:10.3389/fendo.2022.839005.

Cichowski, Sara Beth. “UTIs After Menopause: Why They’re Common and What to Do About Them.” The American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists, Nov. 2023, www.acog.org/womens-health/experts-and-stories/the-latest/utis-after-menopause-why-theyre-common-and-what-to-do-about-them.

“DHEA.” Mayo Clinic, 10 Aug. 2023, www.mayoclinic.org/drugs-supplements-dhea/art-20364199.

“Estrogen.” Cleveland Clinic, my.clevelandclinic.org/health/body/22353-estrogen. Accessed 20 July 2022.

“Genitourinary Syndrome of Menopause.” Johns Hopkins Medicine, www.hopkinsmedicine.org/health/conditions-and-diseases/genitourinary-syndrome-of-menopause. Accessed 18 Feb. 2025.

“Hormone Therapy: Is It Right for You?” Mayo Clinic, 6 Dec. 2022, www.mayoclinic.org/diseases-conditions/menopause/in-depth/hormone-therapy/art-20046372.

“Introduction to Menopause.” Johns Hopkins Medicine, www.hopkinsmedicine.org/health/conditions-and-diseases/introduction-to-menopause. Accessed 18 Feb. 2025.

“Kegel Exercises.” Cleveland Clinic, my.clevelandclinic.org/health/articles/14611-kegel-exercises. Accessed 24 June 2024.

Kim, Hyun-Kyung, et al. “The Recent Review of the Genitourinary Syndrome of Menopause.” Journal of Menopausal Medicine, vol. 21, no. 2, Aug. 2015, pp. 65–71, doi:10.6118/jmm.2015.21.2.65.

Kołodyńska, Gabriela, et al. “Urinary Incontinence in Postmenopausal Women: Causes, Symptoms, Treatment.” Menopause Review, vol. 18, no. 1, Apr. 2019, pp. 46–50, doi:10.5114/pm.2019.84157.

Li, Jingran, et al. “The Fractional CO2 Laser for the Treatment of Genitourinary Syndrome of Menopause: A Prospective Multicenter Cohort Study.” Lasers in Surgery and Medicine, vol. 53, no. 5, July 2021, pp. 647–53, doi:10.1002/lsm.23346.

“Low Sex Drive in Women.” Mayo Clinic, 7 Mar. 2024, www.mayoclinic.org/diseases-conditions/low-sex-drive-in-women/symptoms-causes/syc-20374554.

“Menopause.” Mayo Clinic, 7 Aug. 2024, www.mayoclinic.org/diseases-conditions/menopause/diagnosis-treatment/drc-20353401.

“Menopause.” World Health Organization, 16 Oct. 2024, www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/menopause.

Musicki, Biljana, et al. “Endothelial Nitric Oxide Synthase Regulation in Female Genital Tract Structures.” The Journal of Sexual Medicine, vol. 6, suppl. 3, Mar. 2009, pp. 247–53, doi:10.1111/j.1743-6109.2008.01122.x.

Nappi, Rossella E., et al. “Addressing Vulvovaginal Atrophy (VVA)/Genitourinary Syndrome of Menopause (GSM) for Healthy Aging in Women.” Frontiers in Endocrinology, vol. 10, Aug. 2019, p. 561, doi:10.3389/fendo.2019.00561.

“Ospemifene Oral Tablets.” Cleveland Clinic, my.clevelandclinic.org/health/drugs/19989-ospemifene-oral-tablets. Accessed 18 Feb. 2025.

“Painful Intercourse (Dyspareunia).” Mayo Clinic, 16 Feb. 2024, www.mayoclinic.org/diseases-conditions/painful-intercourse/symptoms-causes/syc-20375967.

“Pelvic Floor Muscles.” Cleveland Clinic, my.clevelandclinic.org/health/body/22729-pelvic-floor-muscle. Accessed 24 June 2024.

“Perimenopause.” Cleveland Clinic, my.clevelandclinic.org/health/diseases/21608-perimenopause. Accessed 2 Apr. 2024.

Portman, David J., et al. “Genitourinary Syndrome of Menopause: New Terminology for Vulvovaginal Atrophy from the International Society for the Study of Women’s Sexual Health and the North American Menopause Society.” Menopause, vol. 21, no. 10, Oct. 2014, pp. 1063–68, doi:10.1097/GME.0000000000000329.

Swenson, Carolyn W., et al. “Aging Effects on Pelvic Floor Support: A Pilot Study Comparing Young versus Older Nulliparous Women.” International Urogynecology Journal, vol. 31, no. 5, Aug. 2019, pp. 535–43, https://doi.org/10.1007/s00192-019-04063-z.

“Vaginal Atrophy.” Cleveland Clinic, my.clevelandclinic.org/health/diseases/15500-vaginal-atrophy. Accessed 3 July 2024.

“Vaginal Atrophy.” Mayo Clinic, 17 Sep. 2021, www.mayoclinic.org/diseases-conditions/vaginal-atrophy/symptoms-causes/syc-20352288.

Wasnik, Vaibhavi B., et al. “Genitourinary Syndrome of Menopause: A Narrative Review Focusing on Its Effects on the Sexual Health and Quality of Life of Women.” Cureus, vol. 15, no. 11, Nov. 2023, doi:10.7759/cureus.48143.

Williams, Nicole O., and Maryam B. Lustberg. “Time for Action: Managing Genitourinary Syndrome of Menopause.” Journal of Oncology Practice, vol. 15, no. 7, July 2019, pp. 371–72, https://doi.org/10.1200/JOP.19.00350.

History of updates

Current version (04 March 2025)

Published (04 March 2025)

In this article

Track your perimenopause journey in the Flo app

-

Log symptoms and get tips to manage them

-

Learn what to expect with expert-led articles and videos

-

Connect with others who can relate to how you're feeling