Everything you need to know if you’re thinking of switching to nonhormonal contraception.

-

Tracking cycle

-

Getting pregnant

-

Pregnancy

-

Help Center

-

Flo for Partners

-

Anonymous Mode

-

Flo app reviews

-

Flo Premium New

-

Secret Chats New

-

Symptom Checker New

-

Your cycle

-

Health 360°

-

Getting pregnant

-

Pregnancy

-

Being a mom

-

LGBTQ+

-

Quizzes

-

Ovulation calculator

-

hCG calculator

-

Pregnancy test calculator

-

Menstrual cycle calculator

-

Period calculator

-

Implantation calculator

-

Pregnancy weeks to months calculator

-

Pregnancy due date calculator

-

IVF and FET due date calculator

-

Due date calculator by ultrasound

-

Medical Affairs

-

Science & Research

-

Pass It On Project New

-

Privacy Portal

-

Press Center

-

Flo Accuracy

-

Careers

-

Contact Us

Nonhormonal birth control: All the options and methods you could try

Every piece of content at Flo Health adheres to the highest editorial standards for language, style, and medical accuracy. To learn what we do to deliver the best health and lifestyle insights to you, check out our content review principles.

Thinking of making the switch to non hormonal birth control from hormonal? We know how overwhelming all of the many, many contraceptive options can be, and we want to help you navigate the change. After all, the birth control we take can have an impact on our lives in lots of different ways, and any decision about it shouldn’t be taken lightly.

So, we’re here to help clear up any initial confusion. With the help of Dr. Ruth Arumala, obstetrician and gynecologist (OB-GYN), we break down everything you need to know about non hormonal birth control, from the difference between hormonal and non hormonal contraception to the benefits and things to be aware of for each type.

Once you’ve learned about nonhormonal birth control, read our guide to hormonal birth control options. Plus, find out how birth control affects ovulation.

What is non hormonal birth control?

Essentially, non hormonal birth control is just what it sounds like: birth control that doesn’t affect your reproductive hormones, which are your body’s chemical messengers. Hormones influence everything from mood to reproduction and sexual function, and with so much riding on them, you can see why some people want to choose a form of contraception that doesn’t interfere with all that.

Non hormonal contraceptives enable a person to prevent pregnancy in a variety of different ways, but they all manage to do it “without affecting cervical mucus production, thinning out the endometrium, or preventing ovulation (when an egg is released),” explains Dr. Arumala, adding that these are the typical ways hormonal birth control methods work.

Hormonal vs. non hormonal birth control: What’s the difference?

In the United States, an estimated 99% of women aged 15 to 44 use at least one form of contraception during their lifetime. That could be one of many hormonal or non hormonal birth control options, so how do you choose? It helps to know the difference between the two. While non hormonal contraceptives contain — you guessed it! — no hormones, hormonal contraception can be made up of either a combination of estrogen and progestin or just progestin.

One further difference is that hormonal contraceptives tend to come with warnings about an increased risk of serious medical issues, whereas non hormonal birth control methods don’t. The health conditions associated with hormonal contraceptives can include “cancers such as breast or uterine cancers, heart disease, liver disease, blood clots in legs or lungs, or strokes,” says Dr. Arumala.

Of course, all this sounds very scary. But it’s important to remember that if you are on hormonal contraception, the chances of developing these conditions are still relatively low, and the benefit of preventing pregnancy generally outweighs any risk.

The benefits and possible side effects of non hormonal birth control

Naturally, there are some benefits in switching. While hormonal contraceptives don’t always come with more side effects (you can experience side effects with some non hormonal birth control methods too, as we’ll detail below), some people feel that they reduce their chances of unpleasant side effects by coming off hormonal birth control.

It’s important to remember that not everyone who takes hormonal contraception will notice any side effects. The impact birth control can have on an individual is just as unique as the person themselves. But we’ve all heard stories about incompatible hormonal birth control, so what are some of the most common offending symptoms?

They can include:

- Headaches

- Acne

- Nausea

- Breast discomfort

- Change in menstrual patterns

- Weight gain

- Mood disturbances

- Irregular periods

- Lower libido

When deciding whether to try non hormonal birth control, it’s important to be aware of disadvantages that could come with it, too. Some methods may require proper planning (for example, those choosing to follow their natural cycle — more on that below), and others require discipline (e.g., the pull out method). That’s why it’s super important to find what works for you, which we’re here to help with!

Types of non hormonal birth control

There is, of course, a huge amount of birth control options to choose from, even when you narrow it down to only non hormonal types. So, it can feel a little overwhelming. Here’s a breakdown of them all, plus advantages and disadvantages for each, to help you make an informed decision about what’s best for your body and mind. But it’s always worth remembering to chat with your health care provider before making any firm decisions about contraception.

Barrier non hormonal birth control methods

You’ll probably come across this phrase a lot when researching contraception. Essentially, barrier methods are the most common type of non hormonal birth control. That’s possibly because they also work in one of the simplest ways. With barrier methods, sperm is physically prevented from reaching an egg, blocking fertilization, which is what leads to pregnancy.

Many barrier contraceptives can be easily purchased online or over the counter at any local drugstore. However, it’s worth noting that condoms are the only barrier methods that prevent the transmission of sexually transmitted infections (STIs), so you need to make sure you’re protecting yourself in other ways if you use another barrier method. There are various types of barrier birth control methods, such as:

• Male condoms (also known as external condoms)

Condoms are still a popular form of birth control, despite the many other alternative options now available. In addition to preventing an unplanned pregnancy, condoms can also protect you against sexually transmitted diseases and infections. They are effective, protecting against pregnancy about 85% of the time if they’re worn before intercourse begins and don’t rip. They’re also easy to use, relatively affordable, and available everywhere.

However, there are downsides, such as bad press. One US study from 2007 found that some people (particularly men) believe condoms reduce pleasure and therefore prefer not to wear them. Condoms can also split (although this only reportedly happens around 2% of the time) and can be less effective if only applied partway through intercourse. It’s also easy to forget that they have an expiration date and must be kept at room temperature, so be sure to consider these things if you decide to use them as your preferred method of non hormonal birth control.

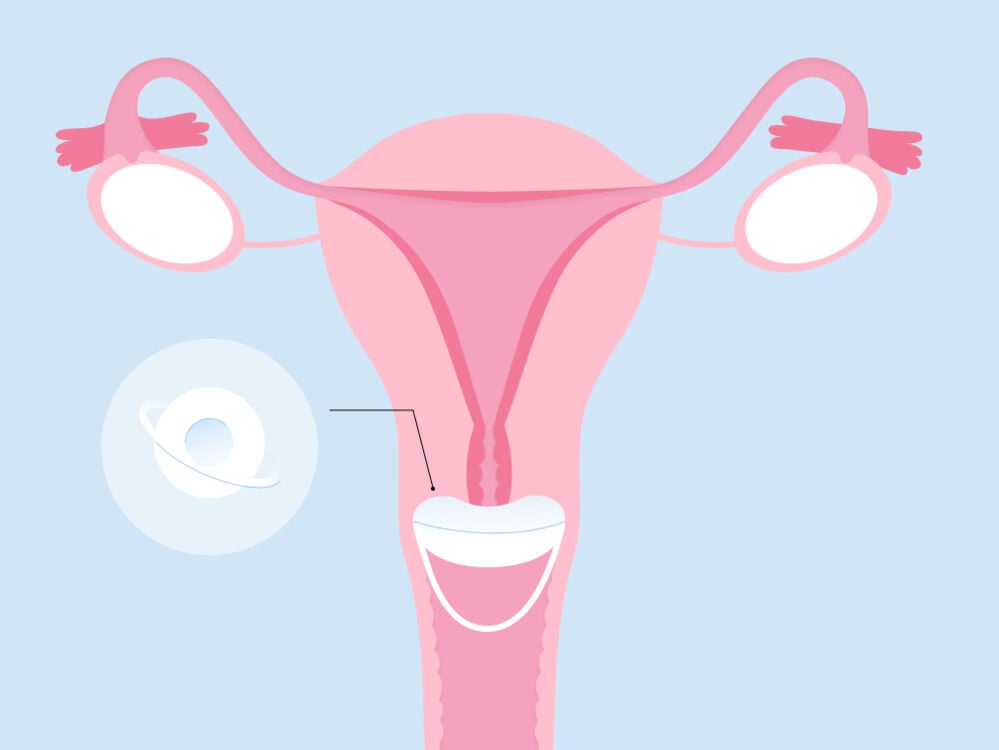

• Female condoms (also known as internal condoms)

A less widely used option, the female condom fits inside the vagina to keep the sperm from reaching the uterus. “It works to prevent pregnancy similarly to the male condom,” explains Dr. Arumala.

Inserting a female condom — or an internal condom — should feel similar to inserting a tampon. Female condoms are designed with a flexible ring on each end. First you squeeze the inner ring. Then you slide it into the vagina as far as it will go (it should be up against the cervix, which is the small, donut-shaped organ that separates the vagina and the uterus). Make sure the outer ring is left outside the vagina. The penis should remain inside the condom during sex. Afterward, twist the outer ring (which keeps the semen safely inside the condom) and pull out the condom gently. You can insert a female condom up to eight hours before you have sex.

One problem with female condoms is that “many patients are not well versed on using [them],” explains Dr. Arumala. They’re also not as effective as other methods of non hormonal birth control; 21% of women using a female condom will still get pregnant in the first year of use.

• Spermicide

Spermicides work in two ways, explains Dr. Arumala. They block the entrance to the cervix and damage the sperm’s movement so they can’t swim up to an egg.

There are lots of different types of spermicide, including gels, creams, foams, films, and suppositories (which are inserted into the vagina). “Nonoxynol-9 is the most common spermicidal agent used in spermicides,” Dr. Arumala adds. This is commonly available over the counter.

With most types of spermicide, you’ll need to wait 10 to 15 minutes after application or insertion for them to start to work. It’s also useful to know that they’re only effective for an hour after they’re put in the vagina. Plus, you need to reapply spermicide every time you have sex. Make sure you don’t wash it out for six to eight hours after having sex.

There are a number of disadvantages to using spermicide, however. “It has to be used in conjunction with a diaphragm or cap [more on both of those below] as it is not very effective alone,” says Dr. Arumala. On its own, spermicide is about 70% effective at preventing pregnancy.

There are a couple of other risks to consider when using spermicide. As Dr. Arumala says, “Spermicide can actually increase HIV transmission. It can also cause bacterial vaginosis, has a funny smell, tastes bad, and can cause allergic reactions to either or both parties.”

• Sponge

A contraceptive sponge is a plastic piece of foam containing spermicide that is inserted into the vagina before intercourse. You wet the sponge with a bit of water and then place it into your vagina up to 24 hours before you have sex. It then acts as a barrier between the sperm and the cervix and is up to 91% effective. Sponges are designed for a single use.

The most important things to know about sponges are that they should be removed at least six hours after intercourse (so they should spend no longer than 30 hours inside the vagina in total), and they share all the same side effects as spermicide.

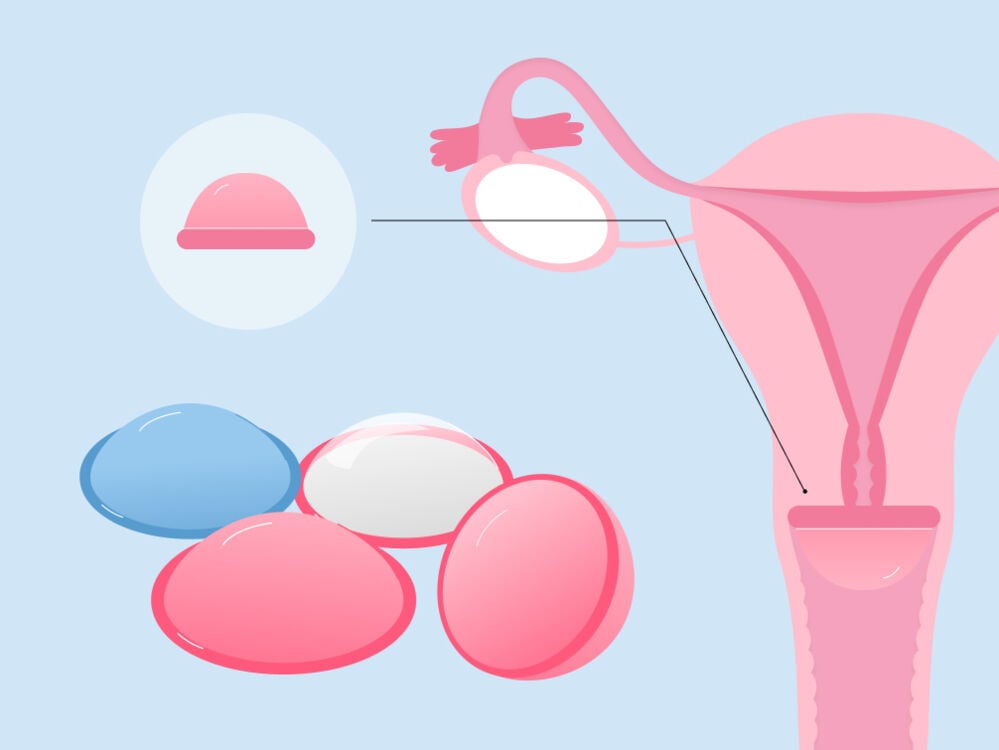

• Cervical cap

“A cervical cap is a reusable silicone device that is inserted into the vagina and creates a suction over the cervix to form a physical barrier to sperm,” explains Dr. Arumala. It must be prescribed and fitted for the first time by a doctor so that it’s the right size for your cervix. Following that, you can insert it and remove it as necessary when you want to have sex, but make sure you get it replaced and refitted every two years.

After sex, you should leave the cap in place for six hours, but make sure you take it out within 48 hours of insertion. You should also know that a cervical cap needs to be used together with spermicide to make it effective.

Cervical caps are not one of the most failsafe barrier methods of non hormonal birth control. It’s also worth noting that caps are less effective if you’ve had a baby. Cervical caps are thought to be about 86% effective in people who haven’t given birth and about 71% effective in people who have previously had a baby. It’s important to know that cervical caps don’t protect you from STIs.

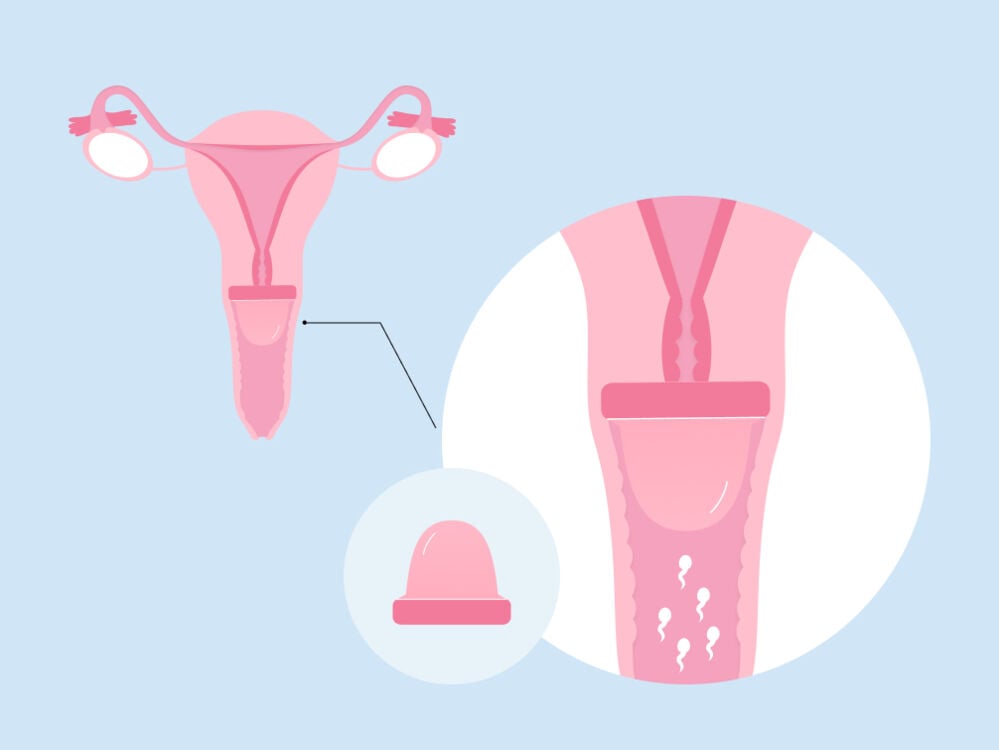

• Diaphragm

A vaginal diaphragm is a small latex or silicone dome-shaped device that “fits in the vagina and over the cervix to prevent sperm from entering the cervix,” explains Dr. Arumala. “A diaphragm needs to be used with spermicide, is fitted by a health care provider, and must be refitted if you gain or lose more than 7 lb.,” she adds.

During the fitting appointment with a health care professional, they’ll show you how to insert and remove the diaphragm yourself. Make sure to ask if they don’t explain. You should always insert your diaphragm (along with the spermicide) at least two hours before having sex, and make sure you leave it in there for at least six hours after intercourse (that’s to make sure the spermicide has enough time to work properly). Aim to remove the diaphragm no later than 24 hours after sex, otherwise you could risk getting an infection. To make sure you’re properly protected, you should get your diaphragm replaced and refitted by a doctor every two years.

If you’re considering a diaphragm as a non hormonal birth control option, know that it’s up to 94% effective depending on how correctly you use it.

Long-term and permanent non hormonal birth control methods

If you are looking for long-term birth control options, there are some non hormonal ones you might want to consider. In addition to being hormone-free, another bonus about these is that you know you won’t have to think about preventing pregnancy every time you have sex. However, as these methods don’t protect against STIs, you will still have to consider this.

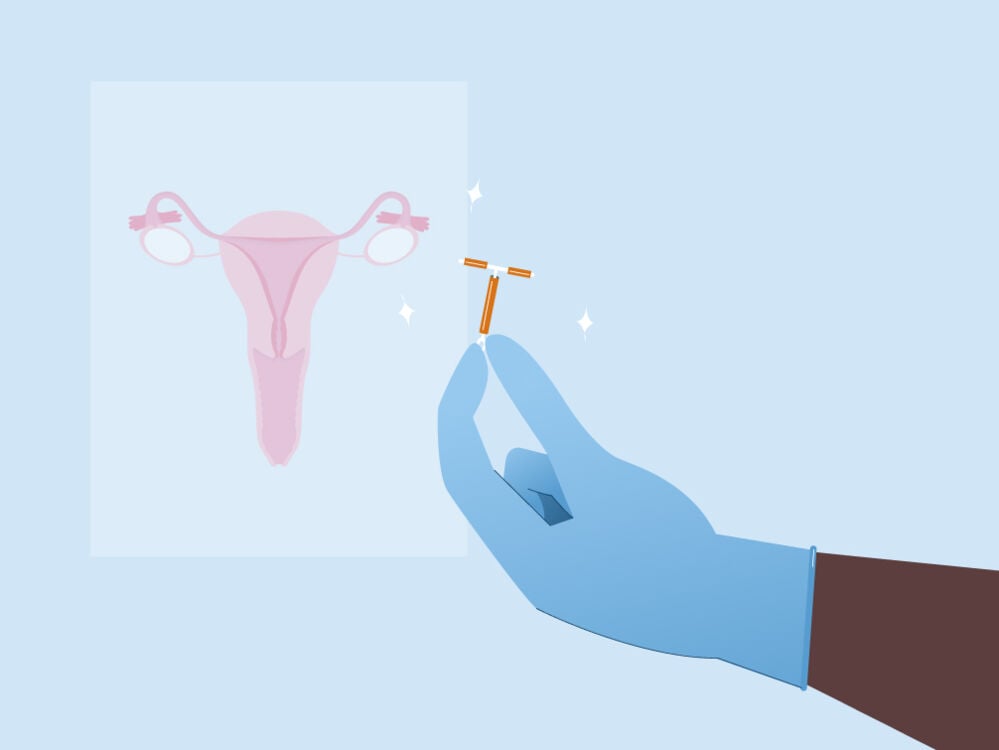

• Copper IUD

The most widely used reversible method of contraception, the copper intrauterine device (IUD) is a device that’s inserted into the uterus. It works by releasing copper particles into the uterus, causing it to become “a hostile environment for sperm,” says Dr. Arumala.

A hostile environment equals a no-no for getting pregnant, which is why the copper IUD is 99% effective. A very safe bet, it seems. “It has to be placed by a health care provider, but lasts 10 to 12 years,” explains Dr. Arumala.

While the IUD can also be removed anytime to return yourself to normal fertility, it does have some disadvantages, including the possibility of IUD cramps, heavy bleeding, and/or spotting between periods. This can sometimes cause people to ask for the device to be removed, so it’s worth being aware that this can happen if you decide to pick the copper IUD as your non hormonal birth control option of choice.

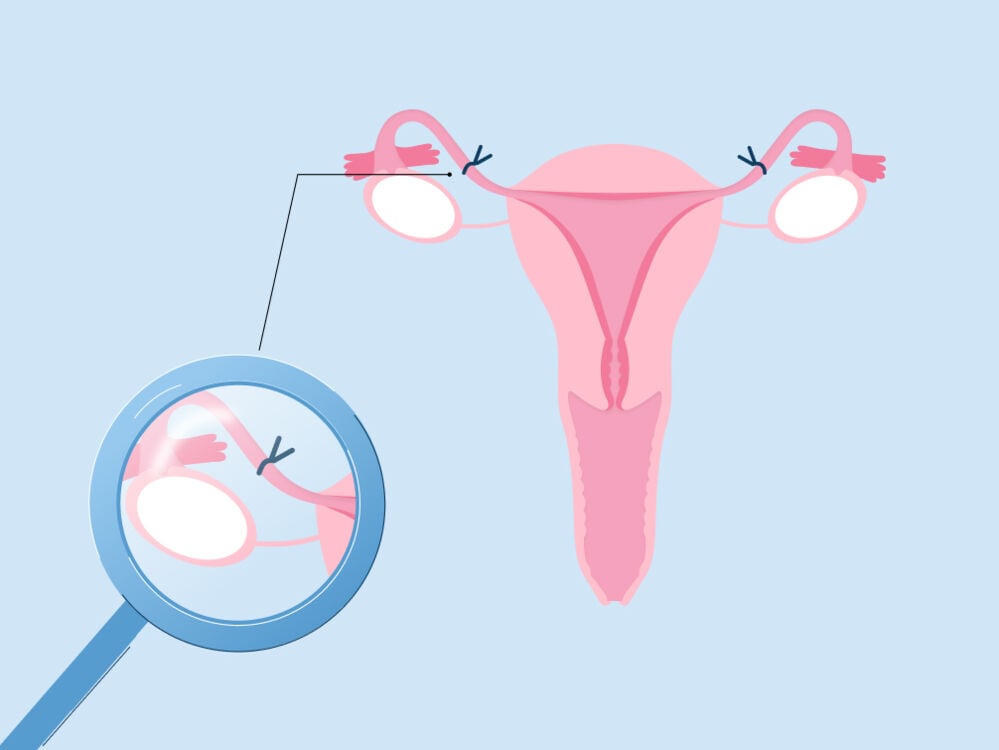

• Sterilization (male and female)

Another option is to choose surgery (sterilization) as a permanent procedure for birth control without hormones. Sterilization can be performed on anyone, but the approach is different depending on anatomy. It’s called tubal ligation for those with female sex organs and a vasectomy for those with male sex organs. It’s one of the most effective forms of contraception, at over 99% effective, but you should be aware that while most methods of female sterilization are effective right away, you’re not always immediately protected from pregnancy with male sterilization. Sperm can be present in semen up to three months after a vasectomy.

Female sterilization is done by an OB-GYN and, depending on the type of procedure, can be done under either local or general anesthesia. On the other hand, male sterilization is performed by a urologist or general practitioner under anesthesia, and patients often only need to come in for the day to have the procedure.

As with any surgery, there are always some risks involved, so it’s important to discuss this with your health care provider if it’s an option you or your partner are exploring. For example, Dr. Arumala also notes that it’s important to be aware that “women who are sterilized have a chance of an ectopic pregnancy [a pregnancy located outside the uterus] if the tubes are not completely removed.”

And don’t forget: As sterilization is a permanent form of birth control, make sure you’re certain it’s the route you want to take before you or your partner take steps toward it.

Other non hormonal birth control options

There are two further birth control options to consider: natural family planning and the withdrawal method. However, neither of these provide any protection from STIs, so it’s important to make sure you consider this to keep yourself safe.

• Natural family planning

If you’re a Flo user, chances are you’re very aware of cycle tracking. Keeping a log of your cycle (however you do it) means you’ll have a better idea of when you’re likely to be ovulating, and you can use this information to help figure out when you’re unlikely to become pregnant. But please note, Flo’s predictions shouldn’t be used as a form of birth control.

You’re most likely to get pregnant during the period known as the “fertile window.” For most people, this is around six days long. That’s because sperm can live inside the female reproductive system for up to five days before ovulation, and once the egg is released, it can survive (and potentially be fertilized for pregnancy) for up to 24 hours.

Based on an understanding of when you’re fertile, you can theoretically try to prevent pregnancy by either using barrier methods or avoiding sex completely during this time.

There are other ways of determining when you’re fertile, beyond simply cycle tracking. These include measuring your daily temperature, known as your basal body temperature (or BBT), as this rises slightly around the time of ovulation. Alternatively, you could examine your cervical mucus (your discharge). Just before ovulation, during your fertile window, discharge becomes thin and slippery, with a consistency similar to egg whites. You can read more about cervical mucus here to make sure you understand it clearly.

However, this isn’t a totally foolproof method, and it’s vital to be aware of that if you don’t want to become pregnant. As Dr. Arumala points out, “Natural cycle planning relies on regular cycles and proper planning.” While it can be effective (up to 99% effective) if followed completely correctly, this doesn’t always happen. For example, many people’s cycles can vary slightly from month to month. With typical use (which accounts for some inconsistency or errors), the rate of effectiveness for natural family planning drops to somewhere between 76% and 88%.

Remember: Ovulation predictions should never be used for birth control.

• Pull out method (also known as the withdrawal method)

“The withdrawal, or pull out, method is reliant on the male partner withdrawing his penis before ejaculation,” explains Dr. Arumala. But here comes that same old sex ed warning you’ve probably heard over and over: It’s not a very reliable method as there can be sperm remaining in the pre-ejaculate, and it relies on the discipline of your partner to pull out in time.

If you want to follow this method, you should know that it’s not the most effective. According to one US study, just over 21% of people using the withdrawal method will get pregnant.

Take a quiz

Find out what you can do with our Health Assistant

Choosing a non hormonal birth control option: Which one is right for you?

OK, so now that you know all the options, what next? Choosing the right non hormonal birth control is entirely personal, and only you can decide what will suit your body and lifestyle best. However, some questions you might want to ask yourself before choosing are:

- Do I want a long-term contraceptive solution?

- Am I willing to have medical procedures?

- Am I disciplined enough to track my cycle monthly?

- Am I happy to apply this method every time I have sex?

If you’re still unsure, book an appointment with your health care provider to discuss it further. Not only can they talk through options, but they’ll also be able to speak to you about your personal preferences.

Switching contraception is a big decision and something you want to be sure will benefit you before you make the change. While we hope we’ve been able to give you some helpful information, really only you and your doctor can know what’s right for you.

Hey, I'm Anique

I started using Flo app to track my period and ovulation because we wanted to have a baby.

The Flo app helped me learn about my body and spot ovulation signs during our conception journey.

I vividly

remember the day

that we switched

Flo into

Pregnancy Mode — it was

such a special

moment.

Real stories, real results

Learn how the Flo app became an amazing cheerleader for us on our conception journey.

References

“Basal Body Temperature for Natural Family Planning.” Mayo Clinic, 3 Mar. 2021, www.mayoclinic.org/tests-procedures/basal-body-temperature/about/pac-20393026.

“Birth Control.” The American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists, www.acog.org/womens-health/faqs/birth-control. Accessed 26 Sep. 2022.

“Birth Control: Forms, Options, Risks & Effectiveness.” Cleveland Clinic, my.clevelandclinic.org/health/articles/11427-birth-control-options. Accessed 26 Sep. 2022.

“Cervical Cap.” Cleveland Clinic, my.clevelandclinic.org/health/articles/17979-cervical-cap. Accessed 26 Sep. 2022.

“Contraceptive Diaphragm or Cap.” NHS, 30 Aug. 2022, www.nhs.uk/conditions/contraception/contraceptive-diaphragm-or-cap/.

Daniels, Kimberly, and William D. Mosher. “Contraceptive Methods Women Have Ever Used: United States, 1982–2010.” National Health Statistics Reports, no. 62, Feb. 2013, pp. 1–15.

Dude, Annie, et al. “Use of Withdrawal and Unintended Pregnancy among Females 15–24 Years of Age.” Obstetrics and Gynecology, vol. 122, no. 3, Sep. 2013, pp. 595–600.

“Endocrine System.” Cleveland Clinic, my.clevelandclinic.org/health/articles/21201-endocrine-system. Accessed 26 Sep. 2022.

“Female Condom.” Cleveland Clinic, my.clevelandclinic.org/health/drugs/17946-female-condom. Accessed 26 Sep. 2022.

“Female Sterilisation.” NHS, 30 Aug. 2022, www.nhs.uk/conditions/contraception/female-sterilisation/.

“Fertility Awareness-Based Methods of Family Planning.” The American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists, www.acog.org/womens-health/faqs/fertility-awareness-based-methods-of-family-planning. Accessed 26 Sep. 2022.

Kaneshiro, Bliss, and Tod Aeby. “Long-Term Safety, Efficacy, and Patient Acceptability of the Intrauterine Copper T-380A Contraceptive Device.” International Journal of Women’s Health, vol. 2, Aug. 2010, pp. 211–20.

Kaunitz, Andrew M. “Patient Education: Hormonal Methods of Birth Control (Beyond the Basics).” UpToDate, 2021, www.uptodate.com/contents/hormonal-methods-of-birth-control-beyond-the-basics.

Mahdy, Heba, et al. “Condoms.” StatPearls, StatPearls Publishing, 2022.

“ParaGard® (Copper IUD).” Cleveland Clinic, my.clevelandclinic.org/health/drugs/17741-paragard%C2%AE-copper-iud. Accessed 26 Sep. 2022.

“Pregnancy: Identifying Fertile Days.” MedlinePlus, medlineplus.gov/ency/article/007015.htm. Accessed 26 Sep. 2022.

Randolph, Mary E., et al. “Sexual Pleasure and Condom Use.” Archives of Sexual Behavior, vol. 36, no. 6, Dec. 2007, pp. 844–48.

“Side Effects of Hormonal Contraceptives.” American Family Physician, vol. 82, no. 12, Dec. 2010, p. 1509.

“Spermicide.” Cleveland Clinic, my.clevelandclinic.org/health/treatments/22493-spermicide. Accessed 26 Sep. 2022.

“Sperm: How Long Do They Live after Ejaculation?” Mayo Clinic, 5 May 2022, www.mayoclinic.org/healthy-lifestyle/getting-pregnant/expert-answers/pregnancy/faq-20058504.

“Vasectomy.” Cleveland Clinic, my.clevelandclinic.org/health/treatments/4423-vasectomy. Accessed 26 Sep. 2022.