If you’re trying to get pregnant and want to get clued up on all things conception, you might want to know how long it takes sperm to reach the egg. A fertility expert explains what goes on inside the reproductive system after ejaculation.

-

Tracking cycle

-

Getting pregnant

-

Pregnancy

-

Help Center

-

Flo for Partners

-

Anonymous Mode

-

Flo app reviews

-

Flo Premium New

-

Secret Chats New

-

Symptom Checker New

-

Your cycle

-

Health 360°

-

Getting pregnant

-

Pregnancy

-

Being a mom

-

LGBTQ+

-

Quizzes

-

Ovulation calculator

-

hCG calculator

-

Pregnancy test calculator

-

Menstrual cycle calculator

-

Period calculator

-

Implantation calculator

-

Pregnancy weeks to months calculator

-

Pregnancy due date calculator

-

IVF and FET due date calculator

-

Due date calculator by ultrasound

-

Medical Affairs

-

Science & Research

-

Pass It On Project New

-

Privacy Portal

-

Press Center

-

Flo Accuracy

-

Careers

-

Contact Us

Here’s how long it takes sperm to reach the egg after sex

Every piece of content at Flo Health adheres to the highest editorial standards for language, style, and medical accuracy. To learn what we do to deliver the best health and lifestyle insights to you, check out our content review principles.

We all know that in order to get pregnant, a sperm needs to fertilize an egg. It sounds simple enough, but there’s more to it than you might think.

If you have unprotected sex in your fertile window, you might assume that you’re guaranteed to get pregnant. In fact, there’s only a 10% to 33% chance of getting pregnant (depending on how close to ovulation you do it), which shows there are a fair few hurdles standing in the way.

If you’re interested in fertility tracking and want to clue yourself up on all things conception, you're probably keen to know the details: How long does it actually take for sperm to reach the egg after sex? What does the journey involve? And how many sperm can you realistically expect to make it all the way?

To answer all these burning sex ed questions (and more), we dug into the research and spoke to fertility expert, reproductive endocrinologist, and Flo Medical Board member Dr. Tiffany Jones for a fascinating glimpse at what really goes on inside after sex.

How does sperm reach the egg after sex?

First things first: Let’s look at where (and how far) sperm need to travel in order to reach the egg.

Following ejaculation, sperm have to swim a mighty journey. They need to travel from the vagina, through the cervix, into the uterus, and finally into the correct uterine tube to locate the egg — no mean feat. All in all, this encompasses a distance of 15 to 18 cm and is, as Dr. Jones puts it, “a very long way for a sperm to swim!”

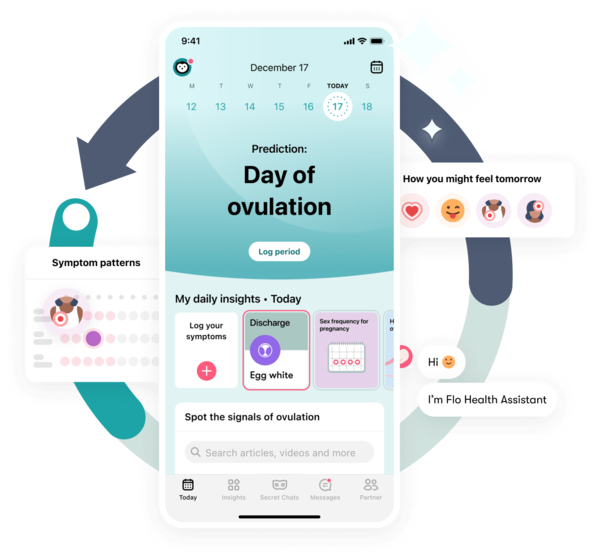

Take a quiz

Find out what you can do with our Health Assistant

How long does it take sperm to reach the egg?

Now that we know how far they have to travel, you’re probably wondering how long it typically takes for sperm to swim the distance. Usually, the sperm reaches the egg within 15 to 45 minutes of ejaculation. However, the process could be much longer than that if you haven’t ovulated yet by the time you have sex, because sperm can live inside a reproductive tract and wait for an egg for up to five days.

While the journey to the egg is certainly long and arduous for the tiny sperm, they do have a helping hand to swim the distance. Within just eight seconds of sperm entering the vagina, the pH in the upper vagina is raised, making it a nicer environment in which to swim. Around the same time, within a minute after ejaculation, the semen becomes a gel, or coagulum. Researchers aren’t yet 100% sure why this happens, but it has been suggested that it can help to keep the sperm near the opening of the cervix. Then, around 30 to 60 minutes later, the gel degrades, and the sperm can begin to swim again. Pretty clever, right?

How many sperm reach the egg, and where does fertilization take place?

Only a very small fraction of ejaculated sperm actually make it all the way to the egg. Around 300 million sperm are typically released during sex, but only about 200 sperm will reach the egg. This is still a pretty big number since we only need one sperm to fertilize an egg.

Not only do these sperm have to swim a great length to reach your egg, but there are also a number of “booby traps,” as Dr. Jones calls them, encountered along the way. Think of these as your body’s natural defenses to make sure only the best sperm reach your egg.

First, sperm that reach the cervix will encounter cervical mucus, which can “bind” and trap the sperm. If you’re trying to conceive, don’t worry. During ovulation, this mucus becomes more watery to allow more sperm to pass through.

Next, sperm that make it through the cervix will then travel to either the left or right uterine tube. This gives them a 50/50 chance of finding an egg, as we ovulate in either our left or right uterine tube each month. Dr. Jones adds that “not all of the sperm will go in the right direction.” It’s estimated that only around 10,000 sperm will actually enter the correct tube.

To make matters even more complicated, the uterine tubes also have “very narrow” openings on the uterus side, once more reducing the number that will successfully reach their destination. However, this is the last hurdle, as fertilization then typically takes place in the uterine tube.

Why doesn’t pregnancy occur every time you have sex during ovulation?

So far, the math doesn’t quite seem to add up: Around 200 sperm from each ejaculation can be expected to reach the egg, yet conception only happens between 10% and 33% of the time when unprotected sex occurs during a fertile window. So the question remains: Why doesn’t pregnancy occur every time we have unprotected sex during ovulation?

There are a number of reasons, according to Dr. Jones. “Not every sperm is capable of fertilizing an egg due to the shape of its head or other defects it may have that don’t facilitate it in penetrating the egg’s shell,” she explains. “Also, as women age, the outer shell of the egg may thicken and harden, making it harder to fertilize.”

This mismatch doesn’t only occur in the body. Dr. Jones adds, “Even in IVF [in vitro fertilization], if an egg and sperm are placed in a dish together (conventional insemination), you can get failed fertilization.”

What happens if sperm reaches an egg that is already fertilized?

Remember those pictures of fertilized eggs you saw in sex ed class at school? More often than not, the fertilized egg was surrounded by multiple, competitive sperm that looked like they might be on the brink of entering the egg at any moment. So the question is, can sperm enter an egg that’s already been fertilized?

Quite simply, the answer is “no,” says Dr. Jones. “Our eggs have a shell, called the zona pellucida,” she explains. “Once the sperm breaks through, the shell of the egg is cemented so no other sperm can come in.”

However, while a sperm can’t enter an egg that’s already been fertilized, it is possible for more than one sperm to enter the egg at the exact same time. This is very rare; “double fertilization” accounts for around 1% of all fertilizations. Unfortunately, in this instance, there is usually too much genetic material for the egg to fertilize normally, and so generally, it doesn’t survive.

Can you feel the fertilization or implantation of the egg?

No, you won’t feel either fertilization or the fertilized egg embedding itself in the wall of your uterus. However, Dr. Jones does explain that you might experience some light bleeding or spotting when implantation occurs, so if this happens, don’t worry. However, if you’re concerned, be sure to book a checkup with a health care professional.

What is implantation, and how long does it take a fertilized egg to implant?

Implantation occurs when a fertilized egg travels down the uterine tube to implant in the wall of the uterus. It can take around 6 to 10 days for a fertilized egg to implant, depending on how far it has to travel. If the egg is fertilized higher up in the uterine tube, it will naturally take longer to move down to the uterus.

Is there anything you can do to boost your chances of sperm fertilizing an egg?

Ideally, you need to have sex no more than five days before ovulation in order for fertilization to occur. You can boost your chances of fertilization by tracking your cycle and having sex as close to ovulation as possible. In fact, one study, published in the Fertility and Sterility journal in 2019, found that women were most likely to get pregnant (41%) by having sex the day before they ovulated.

Aside from that, fertility expert Dr. Jones says she doesn’t know of anything “that would aid the sperm and egg in fertilizing naturally within the body.” There are procedures that can be performed in a lab if you’re struggling to conceive naturally, however, such as an intracytoplasmic sperm injection. This involves sperm being physically injected into an egg but is generally only something that’s suggested for couples who have male infertility issues (like a low sperm count or low motility, for example).

How can you prevent sperm from reaching and fertilizing the egg after unprotected sex if you’re trying to avoid getting pregnant?

If you’ve had unprotected sex and you’re trying to avoid getting pregnant, emergency contraception such as the morning after pill can either stop or delay your egg from being released, meaning it can’t be fertilized. If your egg has already been released, emergency contraception could also work to prevent fertilization or implantation from occurring.

Hey, I'm Anique

I started using Flo app to track my period and ovulation because we wanted to have a baby.

The Flo app helped me learn about my body and spot ovulation signs during our conception journey.

I vividly

remember the day

that we switched

Flo into

Pregnancy Mode — it was

such a special

moment.

Real stories, real results

Learn how the Flo app became an amazing cheerleader for us on our conception journey.

References

“Abnormal Sperm Morphology: What Does It Mean?” Mayo Clinic, 12 June 2020, https://www.mayoclinic.org/diseases-conditions/male-infertility/expert-answers/sperm-morphology/faq-20057760.

Alberts, Bruce, et al. Fertilization. Garland Science, 2002.

Carlson, Bruce M. “Chapter 14 - The Reproductive System.” The Human Body, edited by Bruce M. Carlson, Academic Press, 2019, pp. 373–96.

Center for Drug Evaluation, and Research. [No Title]. https://www.fda.gov/drugs/postmarket-drug-safety-information-patients-and-providers/fdas-decision-regarding-plan-b-questions-and-answers. Accessed 4 Feb. 2022.

“Conception: How It Works.” Center for Reproductive Health, https://crh.ucsf.edu/fertility/conception. Accessed 3 Feb. 2022.

NHS website. “Emergency Contraception (morning after Pill, IUD).” Nhs.uk, https://www.nhs.uk/conditions/contraception/emergency-contraception/. Accessed 4 Feb. 2022.

“Fallopian Tubes: Is Pregnancy Possible with Only One?” Mayo Clinic, 1 May 2021, https://www.mayoclinic.org/diseases-conditions/female-infertility/expert-answers/pregnancy/faq-20058418.

Faust, Louis, et al. “Findings from a Mobile Application-Based Cohort Are Consistent with Established Knowledge of the Menstrual Cycle, Fertile Window, and Conception.” Fertility and Sterility, vol. 112, no. 3, Sept. 2019, pp. 450–57.e3.

“Fertilization and Implantation.” Mayo Clinic, 15 Nov. 2021, https://www.mayoclinic.org/healthy-lifestyle/pregnancy-week-by-week/multimedia/fertilization-and-implantation/img-20008656.

Gould, J. E., et al. “Assessment of Human Sperm Function after Recovery from the Female Reproductive Tract.” Biology of Reproduction, vol. 31, no. 5, Dec. 1984, pp. 888–94.

“ICSI (Intracytoplasmic Sperm Injection).” Loma Linda University Center for Fertility & IVF, 25 Feb. 2015, https://lomalindafertility.com/treatments/ivf/icsi/.

Intracytoplasmic Sperm Injection (ICSI). https://www.hfea.gov.uk/treatments/explore-all-treatments/intracytoplasmic-sperm-injection-icsi/. Accessed 4 Feb. 2022.

Liu, D. Y., and H. W. Baker. “Defective Sperm-Zona Pellucida Interaction: A Major Cause of Failure of Fertilization in Clinical in-Vitro Fertilization.” Human Reproduction, vol. 15, no. 3, Mar. 2000, pp. 702–08.

Sakkas, Denny, et al. “Sperm Selection in Natural Conception: What Can We Learn from Mother Nature to Improve Assisted Reproduction Outcomes?” Human Reproduction Update, vol. 21, no. 6, Nov. 2015, pp. 711–26.

Settlage, D. S., et al. “Sperm Transport from the External Cervical Os to the Fallopian Tubes in Women: A Time and Quantitation Study.” Fertility and Sterility, vol. 24, no. 9, Sept. 1973, pp. 655–61.

Su, Ren-Wei, and Asgerally T. Fazleabas. “Implantation and Establishment of Pregnancy in Human and Nonhuman Primates.” Advances in Anatomy, Embryology, and Cell Biology, vol. 216, 2015, pp. 189–213, https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-15856-3_10. Accessed 1 March 2022

Suarez, S. S., and A. A. Pacey. “Sperm Transport in the Female Reproductive Tract.” Human Reproduction Update, vol. 12, no. 1, Jan. 2006, pp. 23–37.

NHS website. “Vaginal Bleeding.” Nhs.uk, https://www.nhs.uk/pregnancy/related-conditions/common-symptoms/vaginal-bleeding/. Accessed 4 Feb. 2022.

Whitfield, John. “‘Semi-Identical’ Twins Discovered.” Nature News, Nature Publishing Group, Mar. 2007, https://doi.org/10.1038/news070326-1.

History of updates

Current version (17 March 2022)

Published (09 March 2022)

In this article

Get your personal guide to fertility

-

Learn how to read your body's ovulation signals

-

Find daily conception tips from our experts

-

Chat with others who are trying to get pregnant