If you’ve been diagnosed with PCOS, you might be wondering what that means for getting pregnant. Here, an expert answers all your conception-related PCOS questions.

-

Tracking cycle

-

Getting pregnant

-

Pregnancy

-

Help Center

-

Flo for Partners

-

Anonymous Mode

-

Flo app reviews

-

Flo Premium New

-

Secret Chats New

-

Symptom Checker New

-

Your cycle

-

Health 360°

-

Getting pregnant

-

Pregnancy

-

Being a mom

-

LGBTQ+

-

Quizzes

-

Ovulation calculator

-

hCG calculator

-

Pregnancy test calculator

-

Menstrual cycle calculator

-

Period calculator

-

Implantation calculator

-

Pregnancy weeks to months calculator

-

Pregnancy due date calculator

-

IVF and FET due date calculator

-

Due date calculator by ultrasound

-

Medical Affairs

-

Science & Research

-

Pass It On Project New

-

Privacy Portal

-

Press Center

-

Flo Accuracy

-

Careers

-

Contact Us

How to get pregnant with PCOS: Everything you need to know

Every piece of content at Flo Health adheres to the highest editorial standards for language, style, and medical accuracy. To learn what we do to deliver the best health and lifestyle insights to you, check out our content review principles.

If you’ve been diagnosed with polycystic ovary syndrome (PCOS), one of the first things you might have heard about the condition is that it can make it harder to get pregnant. Although that can be true for some, it doesn’t make it impossible — far from it.

If you’re looking for advice on how to conceive with PCOS, you’ve come to the right place. From lifestyle changes to tried-and-tested fertility interventions, there are a range of ways you can boost your chances of getting pregnant. Let’s find out how with a little help from a professor of obstetrics, gynecology, and reproductive sciences.

Getting pregnant with PCOS: Why is it harder?

It’s true that for some people with PCOS, getting pregnant can take a little longer. That’s because PCOS — a common hormonal disorder that affects around one in 10 women of reproductive age — can make some people ovulate irregularly, or not at all. Because ovulation (the monthly release of an egg) is a vital part of getting pregnant, this irregularity can make things tricky — but more on that below.

Scientists still aren’t exactly sure what causes PCOS, but they believe you’re more likely to develop it if it runs in your family or if you have insulin resistance.

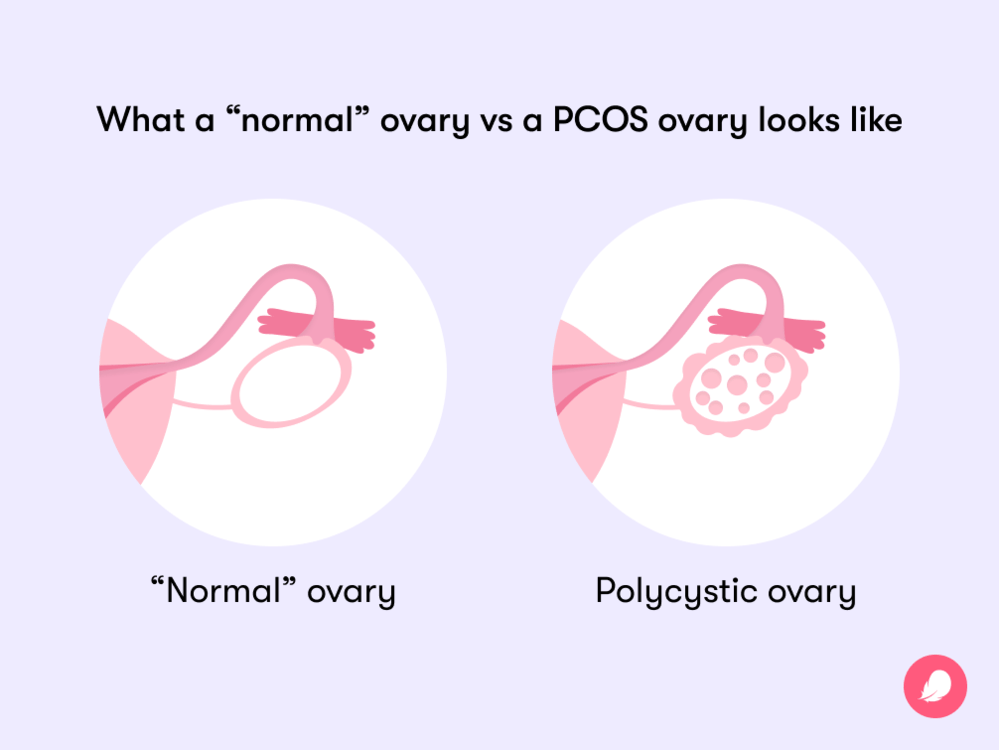

While it’s named polycystic ovary syndrome, confusingly, you don’t always develop polycystic ovaries if you have PCOS. Instead, you may be diagnosed with the condition if you have two of the following three symptoms of PCOS:

- Irregular or missed periods

- A high level of “male” hormones called androgens (which can cause excessive hair growth on the body and face, as well as acne and thinning of hair on the head)

- Polycystic ovaries, which occur when small egg sacs on the ovaries become filled with fluid, known as cysts

But back to how all this can affect your chances of getting pregnant. There are a few main reasons this can happen.

Irregular periods

“In order for pregnancy to happen, you need to have an egg that is released from your ovaries [once a month or so],” explains Dr. Lubna Pal, professor of obstetrics, gynecology, and reproductive sciences at Yale School of Medicine, US.

After ovulation, an unfertilized egg stays in the uterine tubes for 12 to 24 hours before it dissolves. If it’s fertilized by sperm before then, however, it can lead to a successful pregnancy. But getting pregnant with irregular periods can be harder, because if your cycle isn’t consistent, it means you’re probably not routinely ovulating, either. As a result, Dr. Pal explains, “the probability of conception goes down.”

Hormonal imbalances

That’s not the only way PCOS can impact getting pregnant, however. One theory that’s been researched suggests that PCOS can cause hormonal imbalances that change the quality of your cervical fluid, making it harder for sperm to survive.

Weight issues

Further research shows that being overweight may play a role in hormonal disorders like PCOS, which can in turn affect fertility. For example, being overweight is linked to anovulation (when an egg isn’t released during your menstrual cycle), menstrual disorders (such as heavy bleeding and painful cramps), and difficulties with assisted reproduction (like in vitro fertilization, or IVF). However, it’s important to note that not everyone who has PCOS is overweight or experiences weight gain, and many people who are overweight ovulate without a problem.

The impact of stress

There’s also the link between infertility and stress to consider. PCOS and stress are known to be associated. One Iranian study, albeit a small one, found that just over 90% of women with PCOS displayed some level of stress. As Dr. Pal explains, stress along with a fluctuation in body weight (both gain and loss) can alter the signaling of an important cycle-related hormone called gonadotropin-releasing hormone (GnRH). “There are so many factors that can mess up the GnRH, which then translates into menstrual irregularity,” Dr. Pal says. “It’s like a thousand-piece jigsaw puzzle.”

Despite the numerous ways PCOS can impact your ability to get pregnant, Dr. Pal advises that there are ways to try to work around it. “It’s about finding the right strategy that works for you,” she explains.

How much harder is it to get pregnant with PCOS? The statistics

We know that PCOS affects around one in 10 women of reproductive age. Of these, 70% to 80% don’t always release an egg (ovulate) during their menstrual cycle, making conception impossible in these months. This might sound like a high figure, but it’s believed that most women with PCOS will eventually be able to get pregnant if they manage the condition with treatment.

One person who’s part of that statistic is Stephanie, 35, a member of the Flo community who went on to have a PCOS pregnancy. Stephanie says she had “always wanted to be a mum” for as long as she can remember. But following a checkup with her health care provider, after noticing a heavy and irregular cycle, stomach cramps, excessive hair growth, and weight gain, she was diagnosed with PCOS. A scan later found cysts on her ovaries, and, insensitively, she was told it was “highly unlikely” she would conceive naturally.

“It was gut wrenching,” she recalls. “I have always had a motherly instinct, so when you’re told that it may never happen, it sends you on a downward spiral.”

At the time, Stephanie was 27, weighed over 260 lb. (120 kg), and wasn’t actively trying to have a baby. But she still knew that one day she wanted to become a mother. After talking to her health care provider, she was placed on a contraceptive pill to help regulate her heavy and irregular cycle. She was also referred to a weight specialist to establish what a healthy weight was for her, all of which eventually helped Stephanie to become pregnant when the time was right.

Is it possible to get pregnant with PCOS quickly?

When you decide you want to have a baby, it’s normal to feel like you want it to happen immediately. When you have PCOS symptoms, things can be a bit more complicated, but it is possible to get pregnant with PCOS quickly if you manage your health properly. Having said that, there’s no real metric for what “quick” is, apart from your own personal timeline, so try to keep that in mind if you decide you want to start trying.

“Probably 60% plus can achieve spontaneous ovulation through improved lifestyle and weight loss over a span of a few months,” says Dr. Pal. In that instance, provided you produce an egg and your partner’s sperm is good quality, “success rates go back to what they are for an ovulatory woman [without PCOS].”

This was the case for Stephanie, who is now a very proud mom to her 2.5-year-old son. “When I did conceive, it was a complete and utter shock. It took four pregnancy tests and a scan to make me believe [I was pregnant],” she says.

Since managing her symptoms, Stephanie now has a more regular cycle and a lighter flow, and her ovarian cysts have shrunk. Increasing the amount of exercise she did, along with steady weight loss, also had some part to play. “I looked at it like a lifestyle choice,” she says. “I changed my eating habits, and they have continued to change. I do a lot of walking. I’m up to 10 km a day sometimes, and walking also helps mentally, as well as with weight loss.”

At the time of having her PCOS diagnosed, Stephanie recalls that she had “given up hope of having children.” This is a side of PCOS that may take its toll on your mental health. But when the time was right for her to get pregnant, and with the help of a weight specialist, it was something that fortunately happened for her. “I can’t imagine life without my son now,” she says.

We know weight loss isn’t always easy, especially if you have other factors at play, like hormonal imbalances. But the good news is that it doesn’t always require dramatic weight loss to make a difference. “All it takes is a loss of 5% of your excess weight” to improve the likelihood of getting pregnant, says Dr. Pal. It’s all about being at a healthy weight for you, and that looks different for everyone.

Of course, weight loss won’t be the necessary solution for everyone with PCOS who wants to have a baby. If lifestyle changes haven’t proven successful, or perhaps aren’t needed if you’re already active and maintain a balanced diet, a health care provider might recommend fertility drugs such as letrozole or clomiphene to help trigger ovulation. These oral pills are taken in short doses at the beginning of each menstrual cycle, usually for a number of cycles.

Take a quiz

Find out what you can do with our Health Assistant

If these options don’t work, a fertility specialist may suggest intrauterine insemination (IUI), also known as artificial insemination, to help you get pregnant. This is where sperm is inserted into the uterus in an attempt to cause fertilization. Alternatively, IVF is another fertility treatment your health care provider may suggest next, which involves your egg being fertilized in a lab and then transferred into your uterus. You can read more on how that works here.

Tips on how to get pregnant with PCOS

As we’ve seen, it is possible to get pregnant with PCOS. And there are various ways to try to improve that likelihood, ranging from lifestyle changes, such as reviewing diet and exercise, to exploring medical help, including fertility treatment. But there are some other things you can do as a starting point to boost your chances of conceiving with PCOS, such as the following:

Track your menstrual cycle

Whether you have regular periods every month or more unpredictable, irregular bleeds, it’s always worth monitoring your cycle to better understand the way your body works. A period-tracking app like Flo can help here, improving your chances of getting pregnant by predicting when you’re likely to be ovulating — even if you have an irregular cycle. Sign up here.

Give yourself the best possible chance

Wondering what the best age to get pregnant with PCOS is? Generally speaking, women under the age of 35 have about a 30% chance of conceiving in the first month of trying and around an 85% chance in the first year.

Fertility and age go hand in hand. As we age, fertility declines because of a decrease in egg count and quality. Studies have shown that for women aged 35 to 39 years old, the chances of conceiving spontaneously are about half that of women aged 19 to 26 years.

As we’ve seen, for those living with PCOS, getting pregnant can take a little bit longer, which is why it’s probably best not to delay the process if possible. “The longer you wait, the more emotional angst there is,” Dr. Pal explains. “This can cause more irregularity of periods. It becomes a catch-22.”

That said, having a baby is a big decision, so it’s important that you feel ready. Having open conversations with your health care provider to find out all the information you need or reaching out to support services can make a huge difference.

Pay attention to the preconception phase

The preconception phase is defined as the three months before you conceive — and it’s more important than you might think. In fact, Dr. Pal says, “Ideally in utopia, we’d all be paying attention to the preconception phase.”

Why? Well, a few lifestyle changes before actively trying can make all the difference to your chances, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. They recommend eating a healthy, balanced diet, drinking less alcohol, and exercising regularly to help prepare your body for getting pregnant.

Taking at least 400 mcg of folic acid every day is a good idea too, research has shown. One study describes this B vitamin to be “fundamental for growth, especially in the embryonic and fetal stages.” Prenatal vitamins that include iron, calcium, and zinc are also advisable, as these minerals are “crucial to support pregnancy,” notes another study. Some prenatal vitamins also contain folic acid, so we’d recommend speaking with your doctor first to make sure you’re not doubling up.

Optimize your vitamin D levels

Vitamin D may well play a part in your journey to becoming a parent, too. According to Dr. Pal, a deficiency in vitamin D has been linked with “ovulatory dysfunction,” which is the term given to abnormal, irregular, or absent ovulation.

“Women with PCOS have a high prevalence of vitamin D deficiency,” says Dr. Pal, and science agrees. One study found around 67% to 85% of those living with PCOS to be vitamin D deficient. What scientists aren’t sure about just yet is whether or not you’re more likely to ovulate regularly with PCOS if you have sufficient levels of vitamin D. Regardless, The American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists still recommends that vitamin D deficiency is treated while you’re trying to conceive and during pregnancy.

Get your partner checked

Dr. Pal says it’s easy to forget that “pregnancy is a team sport.” So don’t just assume PCOS is the reason it’s not happening for you. Schedule an appointment to get your partner’s sperm checked. As we’ve learned, in order for conception to happen naturally, an egg needs to be fertilized by a sperm. But if the sperm is not strong enough to meet the egg, or if your partner has a low sperm count, it “decreases the odds” that this will happen, says Dr. Pal.

- One-third of infertility cases are actually caused by male reproductive issues, including:

Low (or no) sperm production - Varicocele (an enlargement in the veins in the scrotum that results in a reduction of size and amount of sperm being produced)

- Imbalances in the “male” reproductive hormones (usually due to issues with hormone-producing glands)

How to get pregnant with PCOS: The takeaway

Remember: In many cases, having PCOS doesn’t mean you can’t start a family. Living with PCOS symptoms essentially means there are some factors that can make it harder to get pregnant. But, like with any health concern, it’s important to speak to your health care provider because everyone’s experience is different, and there are plenty of PCOS treatment options.

“In some ways, PCOS is a label that acts as an alert to say, ‘Hey, be vigilant,’” Dr. Pal notes. “If infertility is your concern, use the information to maximize your well-being. Don’t be concerned about it. Just go and seek help because it’s easily, easily surmountable.”

One person who knows that to be true is mom-of-one Stephanie. Her key piece of advice? “Don’t give up hope,” she says. “Seek help and guidance from wherever possible, and don’t ignore it. I am so thankful and grateful for my little boy. It can happen for you; just don’t give up.”

Hey, I'm Anique

I started using Flo app to track my period and ovulation because we wanted to have a baby.

The Flo app helped me learn about my body and spot ovulation signs during our conception journey.

I vividly

remember the day

that we switched

Flo into

Pregnancy Mode — it was

such a special

moment.

Real stories, real results

Learn how the Flo app became an amazing cheerleader for us on our conception journey.

References

Balen, Adam H., et al. “Should Obese Women with Polycystic Ovary Syndrome Receive Treatment for Infertility?” BMJ, vol. 332, no. 7539, Feb. 2006, pp. 434–35.

Boomsma, Carolien M., et al. “Pregnancy Complications in Women with Polycystic Ovary Syndrome.” Seminars in Reproductive Medicine, vol. 26, no. 1, Jan. 2008, pp. 72–84.

Brady, Christine, et al. “Polycystic Ovary Syndrome and Its Impact on Women’s Quality of Life: More than Just an Endocrine Disorder.” Drug, Healthcare and Patient Safety, vol. 1, Feb. 2009, pp. 9–15.

Butts, Samantha F., et al. “Vitamin D Deficiency Is Associated with Poor Ovarian Stimulation Outcome in PCOS but Not Unexplained Infertility.” The Journal of Clinical Endocrinology and Metabolism, vol. 104, no. 2, Feb. 2019, pp. 369–78.

“PCOS (Polycystic Ovary Syndrome) and Diabetes.” Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, 28 Sep. 2021, www.cdc.gov/diabetes/basics/pcos.html.

Dağ, Zeynep Özcan, and Berna Dilbaz. “Impact of Obesity on Infertility in Women.” Journal of the Turkish German Gynecological Association, vol. 16, no. 2, June 2015, pp. 111–17.

Ferrazzi, Enrico, et al. “Folic Acid versus 5- Methyl Tetrahydrofolate Supplementation in Pregnancy.” European Journal of Obstetrics, Gynecology, and Reproductive Biology, vol. 253, Oct. 2020, pp. 312–19.

Giviziez, Christiane R., et al. “Obesity and Anovulatory Infertility: A Review.” JBRA Assisted Reproduction, vol. 20, no. 4, Dec. 2016, pp. 240–45.

“Infertility.” Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, 3 Mar. 2022, www.cdc.gov/reproductivehealth/infertility/.

Łagowska, Karolina. “The Relationship between Vitamin D Status and the Menstrual Cycle in Young Women: A Preliminary Study.” Nutrients, vol. 10, no. 11, Nov. 2018, https://doi.org/10.3390/nu10111729.

Legro, Richard S., et al. “Randomized Controlled Trial of Preconception Interventions in Infertile Women with Polycystic Ovary Syndrome.” The Journal of Clinical Endocrinology and Metabolism, vol. 100, no. 11, Nov. 2015, pp. 4048–58.

Lin, Ming-Wei, and Meng-Hsing Wu. “The Role of Vitamin D in Polycystic Ovary Syndrome.” The Indian Journal of Medical Research, vol. 142, no. 3, Sep. 2015, pp. 238–40.

“Low Sperm Count.” Mayo Clinic, 30 Oct. 2020, www.mayoclinic.org/diseases-conditions/low-sperm-count/symptoms-causes/syc-20374585.

Lynch, C. D., et al. “Preconception Stress Increases the Risk of Infertility: Results from a Couple-Based Prospective Cohort Study—the LIFE Study.” Human Reproduction, vol. 29, no. 5, May 2014, pp. 1067–75.

“Ovulation Signs: When Is Conception Most Likely?” Mayo Clinic, 7 Dec. 2021, www.mayoclinic.org/healthy-lifestyle/getting-pregnant/expert-answers/ovulation-signs/faq-20058000.

“Polycystic Ovary Syndrome.” NHS, www.nhs.uk/conditions/polycystic-ovary-syndrome-pcos/. Accessed 8 June 2022.

“Polycystic Ovary Syndrome (PCOS).” The American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists, www.acog.org/womens-health/faqs/polycystic-ovary-syndrome-pcos. Accessed 8 June 2022.

“Polycystic Ovary Syndrome (PCOS).” Mayo Clinic, 3 Oct. 2020, www.mayoclinic.org/diseases-conditions/pcos/symptoms-causes/syc-20353439.

“Fertility Problems: Assessment and Treatment.” National Institute for Health and Care Excellence, www.nice.org.uk/guidance/cg156/chapter/Recommendations. Accessed 8 June 2022.

Sawant, Shital, and Priya Bhide. “Fertility Treatment Options for Women with Polycystic Ovary Syndrome.” Clinical Medicine Insights: Reproductive Health, vol. 13, Dec. 2019, https://doi.org/10.1177/1179558119890867.

“Session 24: Ovulation and Fecundity.” Human Reproduction, vol. 25, suppl. 1, June 2010, pp. I37–38.

Taylor, Alison. “ABC of Subfertility: Extent of the Problem.” BMJ, vol. 327, no. 7412, Aug. 2003, pp. 434–36.

Vigil, Pilar, et al. “Scanning Electron and Light Microscopy Study of the Cervical Mucus in Women with Polycystic Ovary Syndrome.” Journal of Electron Microscopy, vol. 58, no. 1, Jan. 2009, pp. 21–27.

“Vitamin D: Screening and Supplementation during Pregnancy.” The American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists, www.acog.org/clinical/clinical-guidance/committee-opinion/articles/2011/07/vitamin-d-screening-and-supplementation-during-pregnancy. Accessed 8 June 2022.

Zangeneh, Farideh Zafari, et al. “Psychological Distress in Women with Polycystic Ovary Syndrome from Imam Khomeini Hospital, Tehran.” Journal of Reproduction & Infertility, vol. 13, no. 2, Apr. 2012, pp. 111–15.

Zhang, Erhong, et al. “Relationship between Obesity and Menstrual Disturbances among Women of Reproductive Age.” Heart, vol. 98, suppl. 2, Oct. 2012, p. E156.